Last week I wrote about the origins of my outsider perspective to the art of my own culture, and explained how, now that I’ve finished writing my personal art story, I’m looking around here in Edinburgh to see what I can engage with next. This week it’s a visit the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art.

The way that the exhibits were organised set me off on a bit of a thought experiment about the way that our culture has habitually engaged with the idea of time, both in relation to art and more generally.

Please bear in mind that I’m exploring something that I see, from my newcomer perspective, using frames of reference that come from outside of the contemporary art world. I’m not researching multiple sources to try to get a sense of current debates, but deliberately working with how things land in my own experience. This experience includes decades of academic thinking and sources-backed research, but it’s now is proceeding without that, with only what remains from all of that study in my understanding.

This is the first of a five article exploration, so it may well not be clear where I’m going…. please do comment or get in touch if you want to respond and help me develop my thinking!

Continuing my programme of cultural reorientation, I recently visited the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art, here in Edinburgh. I’m sure I’ll be writing about this gallery frequently. It’s the obvious place for me to begin my re-education and test my prejudices.

I found myself in a beautiful building. Wandering around its rooms, noticing its huge disused marble fireplaces and high ceilings, I wondered what kind of stately home it might once have been. I discovered that the original gallery of modern art, which opened in 1960, was a beautiful Georgian building in the middle of Edinburgh’s Botanic Garden, which I remember visiting in my childhood. Then in 1984 the gallery moved to its present building, which turns out not to have been a stately home, but a refuge for fatherless children. Can you imagine a building being created so splendidly for such a cause today?

When the collection became too large for the building, the gallery expanded into an equally large neo-classical building across the road, which, believe it or not, was built as a hospital for orphans, completed in 1833:

Plans for the replacement Orphan Hospital were drawn up by Thomas Hamilton with an original contract cost of £11,849 and the new Hospital was erected between 1831 and 1833. The managers of the Hospital endeavoured to balance the need to secure a suitable building in keeping with its elevated location at a reasonable cost but which did not resemble a workhouse or prison.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_Two

So many fatherless children and orphans….I imagined a time when there was no pill and no abortions, thinking of all those women having to leave their babies in the streets, hoping some benefactor would find them and take care of them. A time when life expectancy was short, when infectious disease could wipe out a whole family at any point in a child’s life.

The hospital was converted to a gallery in 1999, and now these dark, majestic buildings are called Modern One and Modern Two. I was visiting Modern One.

The first thing that struck me about the upper level of the gallery, was the organisation of paintings from the permanent collection into themes. I spoke to one of the gallery assistants and she said that until recently everything had been organised chronologically, which was perhaps what I had unconsciously been expecting.

The very idea of themes was amphetamine for my brain. If everything is organised into themes, how can you understand how ideas develop over time? How things influence each other, borrow from past experiments, gather disparate elements together and make something new? Then I remembered facing this exact issue when I had to design a year-long Introduction to Hinduism course for the Stirling University Access Course, which is an alternative route of entry to degree programmes for adults who don’t have regular university entry requirements.

The first year, I organised everything in the way I had been taught on my degree; chronologically. We started with the earliest existing evidence of the Indus Valley civilisation around 3,000 years BCE, and slowly tracked forwards in time through the centuries, noting how ideas unfolded, remained mysterious, were brought under changing umbrellas of power and influence. At the end of that first year though, I felt dissatisfied. I wondered how on earth a group of Scottish mature students, immersed in bringing up children, looking after aging parents and working for a living, who had been disenfranchised from the education system at an early age, were supposed to relate to what I had just insisted they digest.

The second year I organised everything around themes. It was a more ethnographic, discovery-based approach. I would start with a video or a miniature painting and work out from it using questions and more images and artefacts, generating explorations and discussions from student engagement and responses. It was much more lively and accessible, and at the end of that year I felt much better about what we had done.

The conventional organisation of time into a linear chronology has come in for a lot of critique in recent decades. The traditional approach to history in our culture has, until fairly recently, been to track time in a forward-moving direction; noting how things develop, and how they build upon and influence each other, one after another. It’s a useful and logical framing, which illuminates how events and norms do indeed affect what comes after them. But this approach also embodies many hidden agendas and unspoken maps.

The most obvious of these is an assumption of progress and development. I’m never sure whether Darwin is supposed to have started this whole thing with the idea of evolution. That doesn’t seem quite right, because surely evolution is movement through time in the interests of survival, which doesn’t, in fact, embody the idea of progress in the sense of things getting better over time, only more fit for the purpose of surviving. Somehow, though, the idea of evolution has come to carry the assumption that the natural order of things is that they develop, in the sense of become better, improved, more sophisticated, superior.

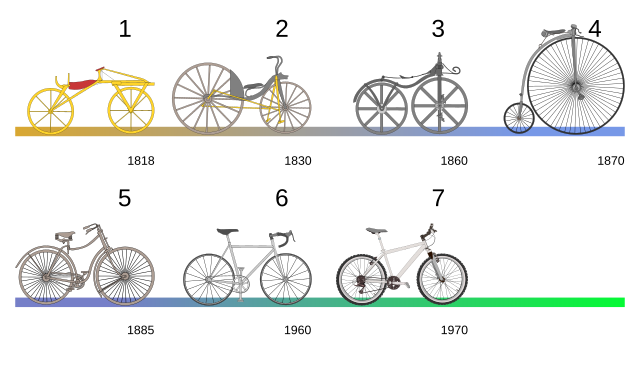

This way of thinking is well-illustrated by this visual of ‘the evolution of the bicycle’:

Humans just get cleverer and cleverer, right? It doesn’t stop at bicycles and refrigerators though. Superstitions are superseded, cultures move from pantheism to monotheism, people become less ignorant, human life gets better, everything improves. Until you see that this is a narrative, a story made up by people who have power; the power to tell their own straight line story and impose it on others for their own gain.

Critiques of straight-line history point out that alongside every such story there are always a hundred missing parallel strands. We could go a step further and say that these hundreds of weft threads are in fact held in place by a thousand unseen lines of warp, running vertically through the horizontal plane, invisibly holding the fabric of time together in ways that the straight-line approach is never able to see. So the single-thread, arrow-of-time approach has a problem, not only because of all the parallel threads that it ignores, but also because it doesn’t acknowledge the myriad vertical strands which are actually holding everything in place.

A theme interrupts the horizontal narrative by picking across the cloth according to one idea, collecting the end results of many disparate processes. It removes all contexts and forces the viewer to examine only what it’s chosen to frame; ignoring linear movement through time and the specifics of location, it says, look, there’s an underlying shape here, a form that things keep falling into. In art it says, look at these different pieces of art from this perspective, and see what happens for you.

Isn’t this what art is supposed to do, speak on its own terms, as itself? Exist as a physical creation, a concrete emergence into time and space? So many things in me want to agree with this. I am utterly resistant to the conceptual turn, the cerebral overactivity; the artspeak essay, the specialist vocabulary, the exclusionist practices, justifications and explanations.

If the problem with the linear assumptions of chronological history is the artificial neatness it creates by ignoring so many threads, the theme can certainly work to interrupt the Enlightenment view of an ever-progressing world. A theme prises you out of any developmental expectations you may hold and forces you to swim in the sea of the present; to experience your own perceptions, feelings, responses. Context, in this situation, is what you yourself bring (including your own knowledge, of course, of the history of art…).

Despite my interest in the importance of context in so many situations, I can’t help but feel that, with art, there is a strong argument that this is exactly how it should be.

You can probably guess that I am not entirely finished with this topic…. I hope you’ll bear with me, and, as I said above, please do comment or get in touch with your thoughts so that I can explore this further. I’m trying to imagine what the implications might be of different ways of thinking about time, history and context for both receiving and making art. Perhaps it’s a straw man, and there’s nothing new at all about my direction! But it’s new to me, so I will continue to explore….

I really like how you connected the way exhibits are arranged with how we think about time. Your story abot switching from chronological to thematic teaching really hit home. Themes can reveal patterns and connections that a straight timeline might miss.

What thought provoking writing - thanks Tamsin!

When I researched history of science I learned that history should not be a looking back from the vantage point of the present, where it can be recited as a timeline of events. Judging from the knowledge of now forces a narrower picture where only events that fit now can be considered. However difficult it may be, a (good) historian of science tries to be present in the past, and see the ‘now’ that was then, from which happenings, discovery, knowledge, insight, emerge. There is a timeline of 'then', next then, ... to now etc. but history viewed as the present in the past becomes an active present, alive, seen in its own then. That makes sense to me in a way that is similar to the thoughts you have stirred. Is it that the notion of theme gives all sorts of associations etc that are not there if the thought process is timeline bound, but are there because a theme allows a kind of empathy?

I think this ialso links to the way psychoanalysts talk about the "past in the present" ... just thinking as I'm writing ... finding that theme that is in someone's inner world ??

Empathetic resonance with whatever is /was there brings much wider/deeper pictures of both then and now. So much is lost by chronology as a list, the old cause-effect rationality stuff.

It must be obvious that I know nothing about the history of art so when at the galleries I wouldn't even know that the hangings were chronological unless the label said so. I am loving what I find in your explorations.