In my last piece, The pine tree, I wrote about living in the Himalayas and working at the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA). Of rhododendron forests, and the Dalai Lama’s old court dance master, allowed out of Tibet for just six months to pass on his knowledge (oh, did I not mention him?). Of watching ancient traditions of Tibetan Opera being practiced in full costume on the basketball court in the shadow of the snow peak; of four generations of Tibetans gathered around a TV in the evening watching a BBC historical documentary about life in Tibet before the coming of the Chinese.

I didn’t write about the funeral of the Institute’s cow man, how the students carried his body through the forest in sparkling sunlight down the mountainside to his pyre by the river, the red-robed monks chanting as his body was tipped onto the flames. And I didn’t write about my classroom, once a day, ten students or so, ranging in age from five to fifteen, some of them recent arrivals from Tibet, who had no experience of classrooms; grimy and displaced, looking at me quizzically.

I also didn’t talk about the shock of arriving amongst such poignant beauty and cultural fascination to find myself in the midst of deep horror (evenings spent with friends and whisky listening to passionate discussion that I couldn’t follow linguistically but did in every other way); the complicated refugee politics of this community in exile, living clustered around the towering figure of the fourteenth Dalai Lama, fighting daily in their hearts and souls for the return to their homeland.

I was wide open when I arrived, after three years of living amongst the sunflowers and red earth of Umbria, and years of planning and slowly burning all the boats and bridges I had ever had behind me. This was it, for me. The beauty of the mountain, the welcome I felt from the community, purposeful work without the endless stress of an overcrowded timetable, the slow unthawing of my art.

And then it came to pass ... that the Indian authorities refused to extend my visa. This had never really been a possibility in my mind. When I first planned the move, there were no visas for British people, then Indira Gandhi was shot and they were introduced. But somehow, this being India, I must have assumed that strings could be pulled. It turned out that they could not. I was in shock. I had nothing to go back to, no home, no base. Clearly a dangerous state to be in.

At that moment I was approached by someone I thought was a trusted friend of a friend and asked if I would like to go and teach in a school in Tibet. It seemed perfect, though I had few funds and no idea what it would involve. I went to live with a Tibetan family in Switzerland while waiting for the paperwork to be processed, trying to write a book about my experiences and the Tibetan situation. The Swiss Red Cross were involved, and it was all going smoothly. The wait eventually became so prolonged that I asked them if I could go and wait in India (waaaaahh, such naive, idealistic passivity...) and they said yes, so back I went to Dharamsala. But within days of arriving, I realised that something was deeply wrong.

The atmosphere had changed, people seemed to be looking at me oddly. Where I was going to teach in Tibet was the traditional seat of the Panchen Lama, the second most important lama in Tibet after the Dalai Lama, and there were complicated historic rivalries amongst differently affiliated groups. The current incarnation of the Panchen Lama had been recognised after the Chinese occupation, and was and still is a controversial figure. It turned out that the community was not in a mood to be generous to yet another naive, idealistic, clueless foreigner in their midst, and I was now regarded with suspicion, seen as a potential collaborator. I took advice, began to understand what was going on, and pulled out of the project. But the damage had been done.

Art Pilgrim has a quite a tough time for the next few years. She takes off for Japan to replenish her funds. The chutzpah is unbelievable. She buys a one-way ticket via Hong Kong, and there uses the last of her money to buy pseudo-posh suits, pencil skirts, fancy shirts and shoes. When she gets to Tokyo she is wearing the suit, and she pushes her passport across the desk with a hand bearing a gold, garnet and pearl ring belonging to her grandmother, which for some bizarre reason she has with her. If they find out that she has a one-way ticket, she won’t be allowed in. But it works. She heads for a foreigner’s ryokan and after settling in decides to go for a walk. She’s ten minutes or so away from the ryokan when she realises that she hasn’t taken note of any landmarks. With no English in sight, everything is a mass of Japanese and Chinese characters, billboards and neon signs. She is completely and utterly lost.

She stays in Tokyo for two years, at first working three jobs; proof-reading by day and teaching at night. She finds relief in her lunch hours in the grounds of the gaspingly beautiful shrines that exist in many areas of the city, soothed by the trees that line the paths up to the low-hanging curved wooden roofs of the shrines.

Inside it’s dark; the smell of fresh green tatami matting, the fluttering of woven paper offerings hang down white against the gloom. She buys exquisitely embroidered talismans in the shrine shop in gold and purple, orange, red and silver.

Eventually she lands a prestige job working for a company which trains simultaneous translators for NHK, national Japanese television. It’s high profile work and terrifying, but it’s a step towards finding some kind of ground again. In the evenings, in her traditional old wooden house, sitting on the unchanged tatami matting (the only kind of accommodation that foreigners can afford to rent in Japan; the Japanese require fresh new tatami every time and rarely move), she reads every Mishima novel in translation and two biographies. She walks the streets of her neighbourhood, past tofu shops and fish vendors, endlessly tempting restaurants behind their slit linen screens, too shy to go in.

Sometimes she goes for a bath at the local sento (no private bathrooms in the old house), where women stare at her and point; she dips herself into hotter and hotter communal tubs until everything is sweated away for another day.

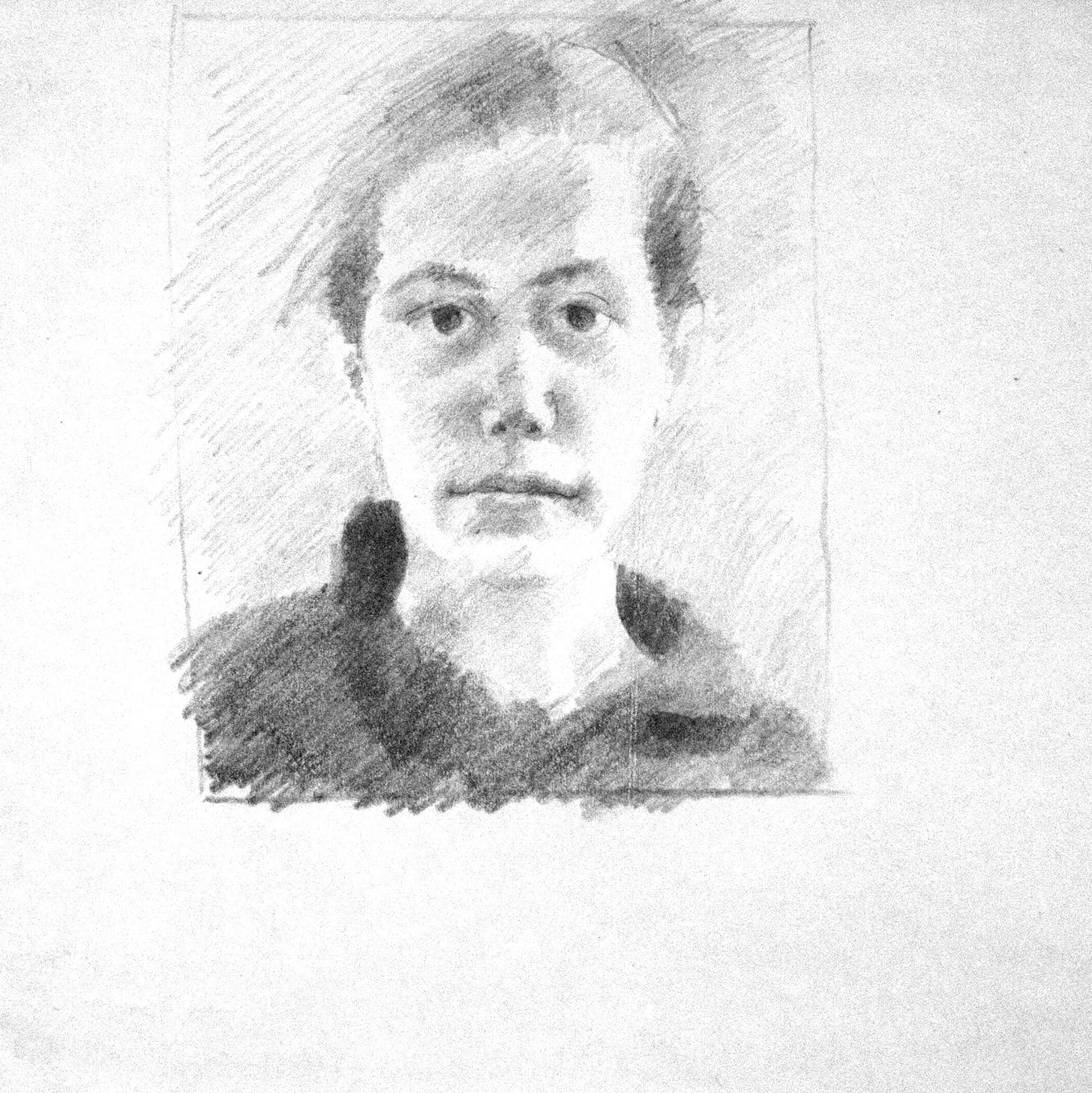

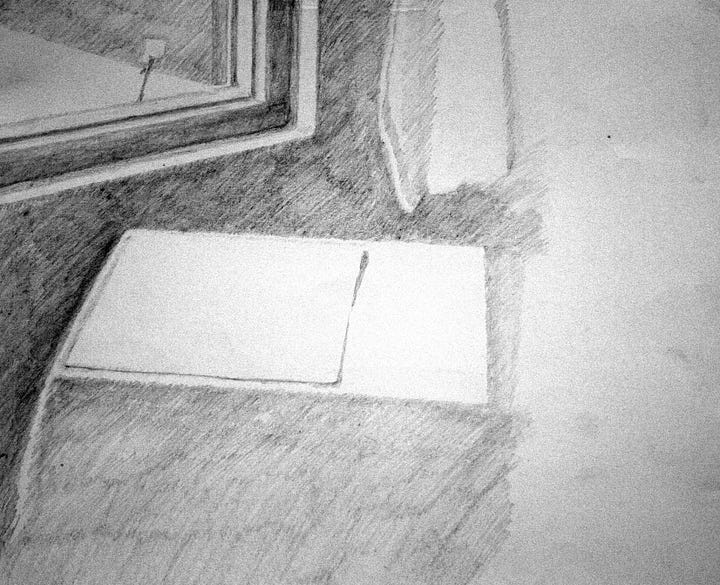

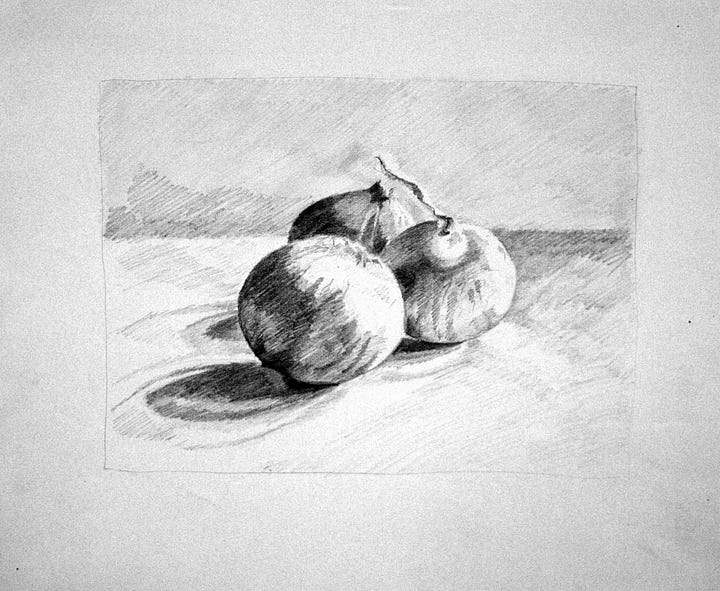

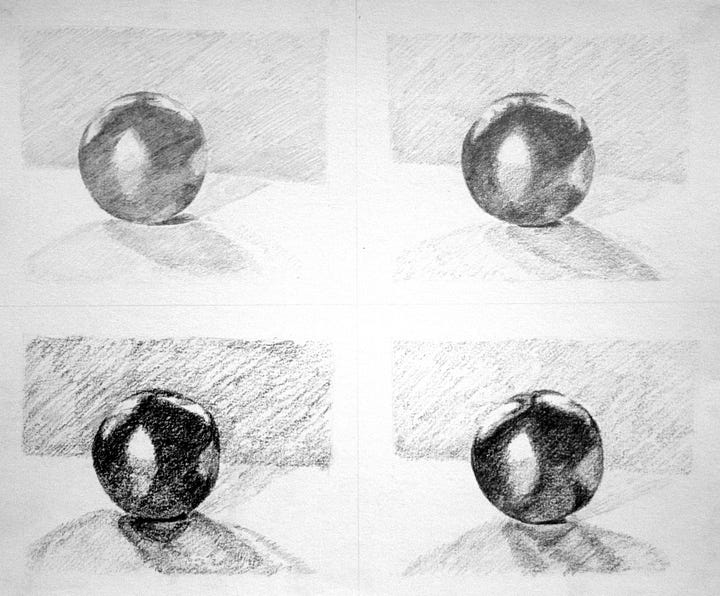

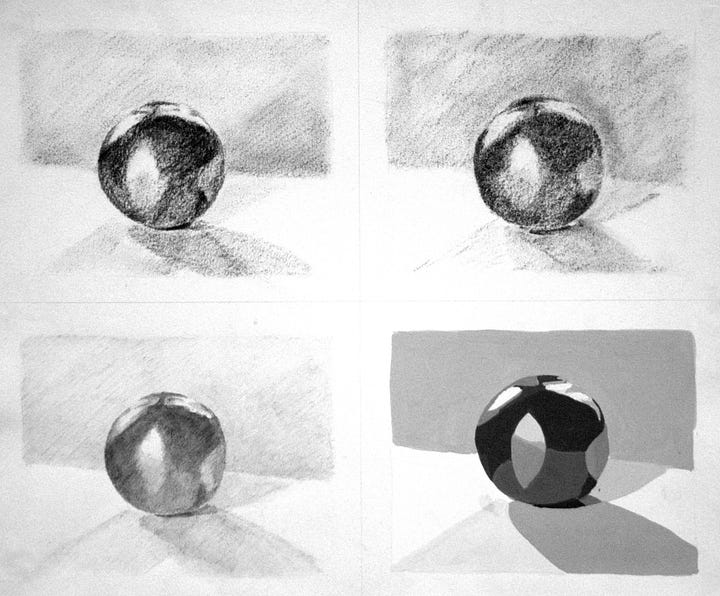

By a convoluted path, at the end of the two years, I arrive back in Dharamsala, in a final attempt to find my old magic and peace (which of course is not there at all, but that’s another story). Hundreds of Western tourists passed through McLeod Ganj at all times, seemingly oblivious to the plight of the Tibetans, and usually I never talked to any of them. But for some reason, one day I meet a young artist called Lindsay. Lindsay is wild and British, yelling back at jeering Indian men when we travel together to a remote Himalayan village, in contrast to my carefully practised skills of invisibility. I can’t remember if she had failed to get into art school or just avoided it, but she had apprenticed herself to someone in England who had trained her in traditional, ‘old master’ skills of tonal drawing and painting. She was also a fabulous cartoonist; a free artist following her nose, unaffected by art school restriction and hype. Years later she gets into the Slade and the last I hear of her she’s just done an installation about her grandmother using photos and light and it makes me want to cry. But at this point she’s drawing everything wonderfully, and she proceeds to teach me what she’s learned. I am awed by her skill, and for a short time I become joyfully immersed in all of her exercises; tonal studies without any lines, black and white paintings that study gradations of tone.

I remember drawing and painting a plum in sixteen different ways. The more I looked, the more I saw that a plum doesn’t just have a shadow, it has at least three or four, all of different tonal densities, because of all the different light sources that are falling upon it.

The free line was nowhere in sight, but it was wonderful development for my skills of looking and seeing.

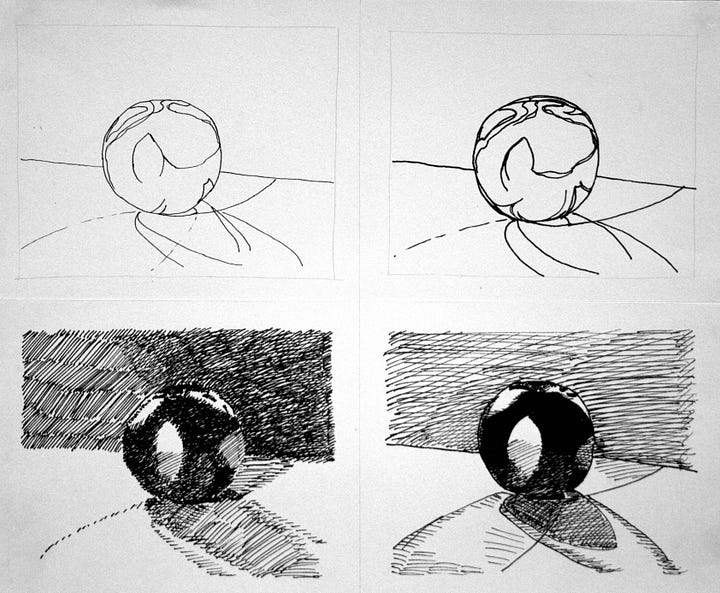

Here is Lindsay showing me how to conjure her face without drawing a single line:

For all my questions about what art can do after Malevich, I find this utterly magical to this day.