Death by White on White,1918

How the neat chronology of a Eurocentric art education devoured my soul

The Pre-Professional course at the Berkshire College of Art consisted of full-time art practice and tuition, with lectures for an Art History A level. Sixteen years old, I had left home and was living in the Girls Friendly Society Hostel in Reading, along with many other women who I never saw, apart from occasionally spotting someone ironing their hair in the common room. It was a gloomy Victorian house that stretched over four or five floors, hallways lined with dark oak panels, a sweeping oak staircase up the middle. I lived in a small room on the top floor, looking down at the street as I fed my gas meter with coins and wondered how you were supposed to study art and architecture.

My schooling had been interrupted due to family disturbances and constant moving and I had no idea about anything. So I let myself be a sponge, absorbing the slides and lectures, marvelling at the history of coloured riches that was gradually laid out before me.

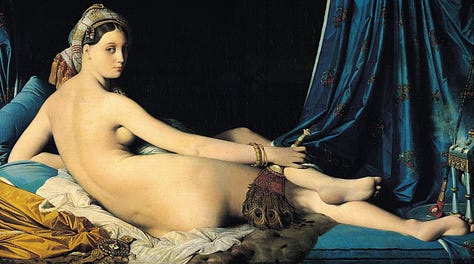

It was a beautiful, logical picture of reactions and counter-reactions; each new move a thrilling ground-breaking rejection of all that had gone before. David and Ingres, reacting to what were seen as previous excesses; Gericault and Delacroix (and Turner) reacting to their stark neo-Classicism with passion and movement and colour. Then the Impressionists, turning away from Delacroix and Gericault’s rich naturalism, heavy oils and darks; excited by science and the study of light, fragmenting paint across the surface of the canvas, letting their brushstrokes show, letting colour explode.

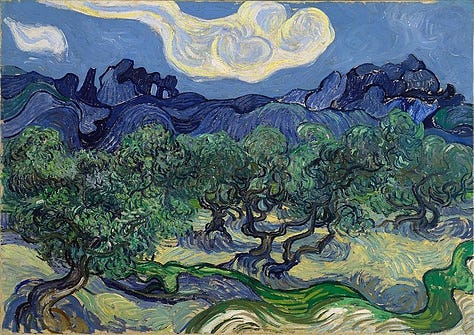

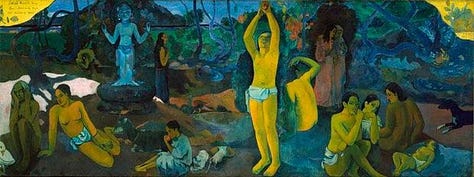

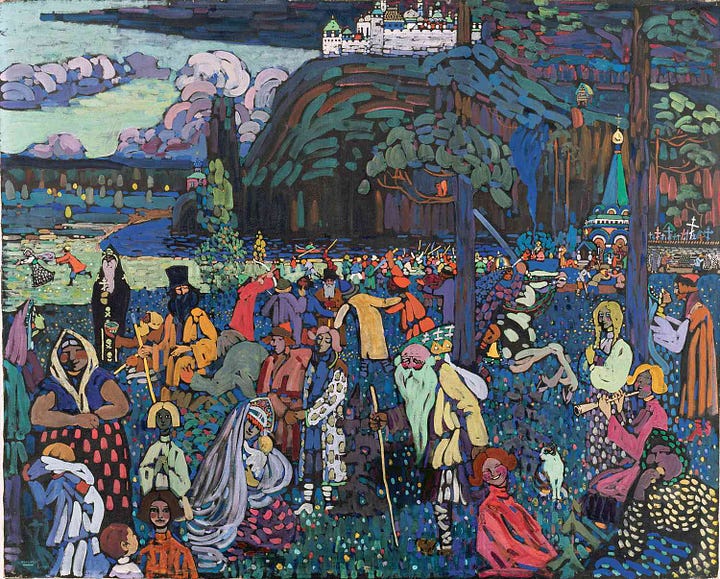

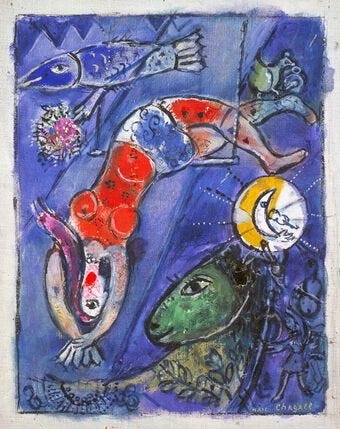

And then, moving neatly on, Post-Impressionism, Van Gogh and Gaugin taking colour even further, moving several steps further away from naturalism, followed by Cezanne, Matisse, Nolde, Chagall, Modigliani, Schiele, Marc, Picasso…

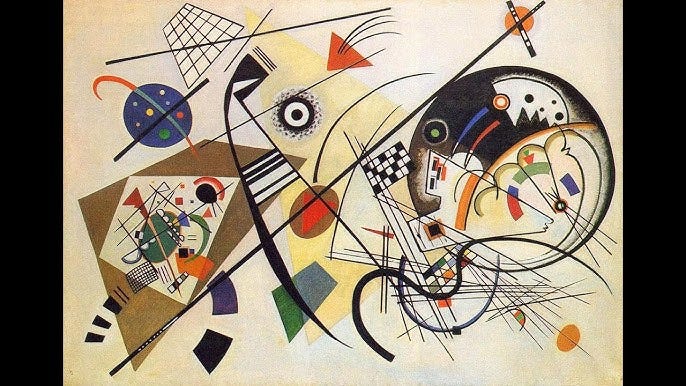

... all playing with how far they could push naturalistic representation until Cubism began to fracture it, and finally we arrived at the cool, rarefied air of pure abstraction.

What mattered in art was not imitation of nature but expression of feelings, through choice of colour and line.

Gombrich, 1989:451

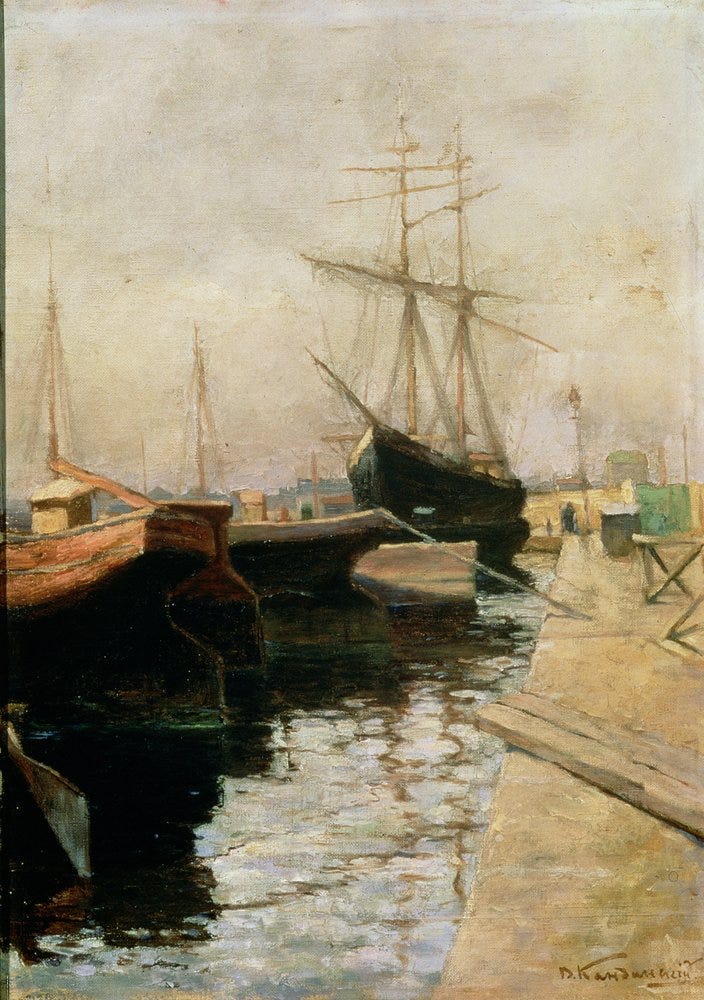

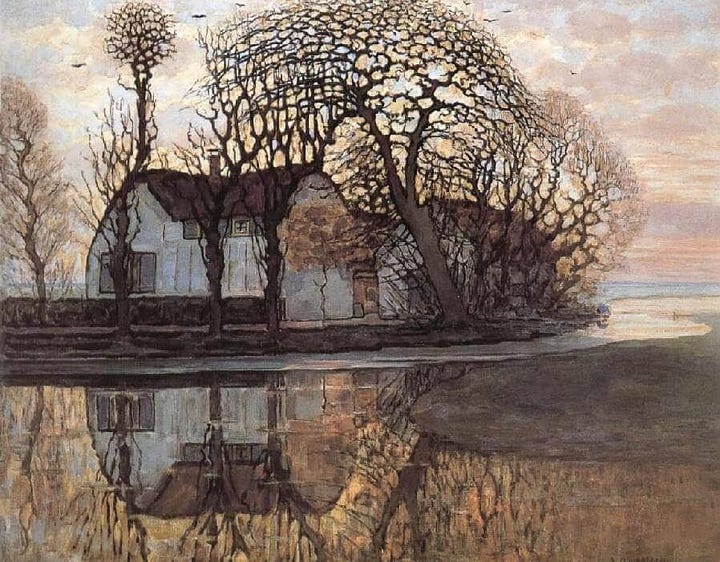

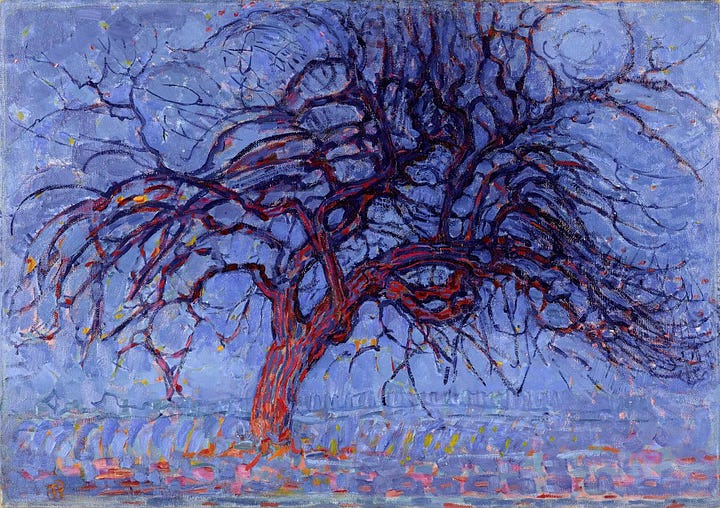

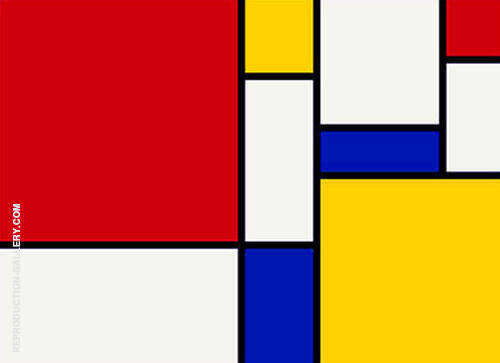

The way it was presented, everything seemed to make sense. Kandinsky, Mondrian, Picasso, had all learned to create highly-skilled representational paintings in their early years. It was clear from looking at their paintings over time that they had only gradually moved away from literal responses; there were years and years of work and dedication on the path to ‘pure abstraction’ .

One day we were shown a Malevich painting that consisted of a white square on a white ground:

I don’t know if I heard someone actually declare that painting was dead, but the beautiful, logical chronology of the history of art appeared to have finally arrived at its destination, which turned out to be the beginning of it all – a blank canvas. Linear European time had looped back and become Indian time, except that I couldn’t find any sense of circulation or reincarnation. It was a straight line. Gaugin and Matisse had the Impressionists to react to, the Impressionists had had the Academy; everyone who went before had had something to kick against, a wide empty field in front of them, with no footprints on it at all. But now it had all been done. All the fields had been explored, and were now getting churned up from so much traffic. It seemed to be a free-for-all, where anyone could do anything, for any reason. Instead of seeing this as freedom, for some reason it troubled me. It seemed trivial, superficial. What had happened to art? And what was the point, now?

Towards the end of the course, I remember being instructed to make some abstract work. I can see grey squares on a plain surface, with patches of green. It felt weird and pointless. Wasn’t I supposed to learn to paint from life first? Wasn’t I supposed to slowly explore through working with paint and surface in response to the light and shadow of the world, over and over, until I began to find my own interpretation, my own connection to it all? But it was not to be. It was 1975, and St Martin’s School of Art in London, my next stop, was committed to abstraction and performance art (I wrote a bit about that here).

I completed the Foundation course, got into the Degree, but realised that if I stayed I would fail everything. I got permission to take a year off so that I could go travelling, hoping that this might give me some answers.

On my art history course, I had noticed Rousseau, and Chagall, and Ernst, but I don’t think I could make sense of what was guiding them. I certainly didn’t know how to draw from that kind of well myself. I was 17, keen, but I had no ground to stand on that I could call my own.

Interesting how you saw that art came full circle, to abstraction and interpretation, to oblivion so to speak! Nice read!