Some months after leaving art school, I was staying in a house in Argyll, Scotland, when I picked up a piece of wood covered in lichen. I found myself reaching for some paper and charcoal, transfixed by the world I saw there. Tiny, exquisite rolls of curling pale green spiralling over underlying stains of yellow ochre, softness and hardness; a living thing that looked like a frozen wave, living off another living thing underneath it. The wave held me in its gaze, and it said, ‘Look, look some more, do you feel it?’

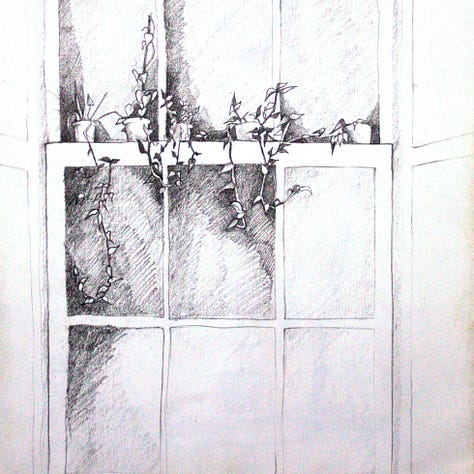

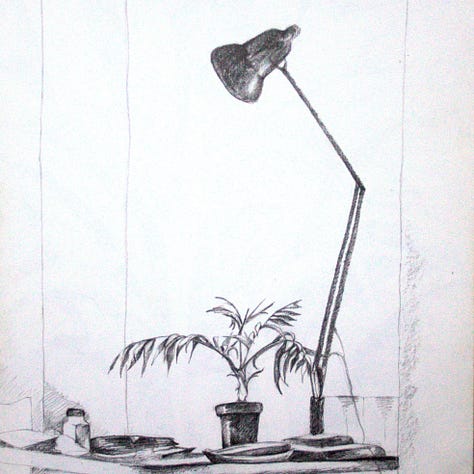

Things went quiet after that, for the next three years. I had returned from my first round the world trip and was living in a flat in Edinburgh, waiting for my English teaching course to start. Late one night, for no particular reason, I looked up at a house plant that I had placed in the middle of the big Victorian window, its leaves and stems falling down in front of the panes of glass. It was dark outside, and raining. Suddenly I saw and felt what I was actually looking at. Alive. Electricity. Something. That night I drew until the early hours, and in the days that followed everything in the room became a fascination. Cotton wool in my ears against all that my art school tutors had told me not to do, I followed the shapes and tones, captivated.

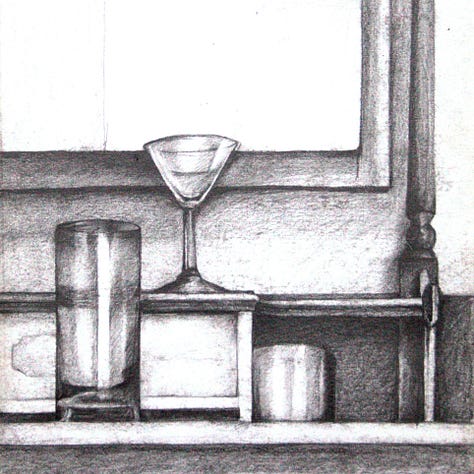

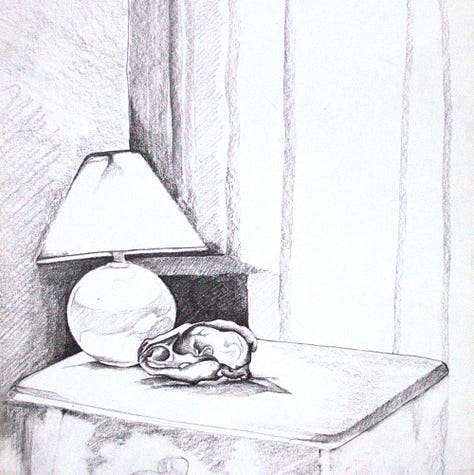

The magic of light and dark soothed me. I began to thaw, slowly understanding that the mystery and wonder that had seeped into me from the earthen streets of Korean villages, the ceramic curves of Taiwanese temples, the crowded alleys of Hong Kong, were also present in the unremarkable objects on my chest of drawers, the shapes in my fruit bowl.

I was 19 when I drew the lichen wave, 23 when I saw the trailing tradescantia plant. I was an art school dropout with no profession or skills but it didn’t matter. I knew from my father’s books on Egyptian and Cretan art that somewhere in the world there were people who sculpted figures of fierce women with snakes in their hands and dresses cut below their naked breasts; I knew there were women with luscious long perms bending backwards towards the sky. As a child, I had been a regular visitor to the Chamber’s St Museum in Edinburgh, my home town. I used to make drawings from Egyptian friezes, noticing that often animals seemed to be more important than people; that sculptures and paintings showed human bodies with eagle heads holding up the sun, and snakes with wings balancing the moon. The world felt like a vast cauldron of wonder, waiting for me to discover it.

I went first to Italy, where I lived for three years, teaching English to pay my bills and drawing and painting everyday objects and landscapes whenever I could. But the images were strangely unsatisfying. I’ve written before about how every time I finished something I would look at it and think, no, not this, it’s not this, it’s something else.

But there was one exception. It was a small drawing done with a red biro on a scrap of paper. I don’t know why I made it, it was a doodle, my attention had been elsewhere. But when I looked at it more closely, I felt that strange movement again. I had no idea what it meant. The line was spidery and free, wandering all over the place with no apparent plan or intent, as if ending up forming a man and a tree had been a casual accident. It felt like they had been spewed out of some kind of primordial goo into a previously unknown space between the worlds. And I couldn’t stop looking at the line that connected the man to the tree.

Some beautiful writing here Tamsin. When I am back in Edinburgh I now also want to introduce you to one of my friends, who is also an artist and thinking about starting a Substack. what a great way to weave together all your adventures - through lines and stories.

Glorious and fascinating …. and that line? Still there it is … I love that, in your telling, I feel more well travelled

I have never seen such things …

I remember an art teacher ( not my art teacher - he just let me use his dark room when I was dogging double Chemistry) saying to me that his art seemed to come from responding to what felt like the pull of a thread or line that he could never quite place but that he felt in some way compelled to pull back. I was always intrigued by the line and the unknown source and what was birthed in reciprocation.