When you force it, you block it

Making art and the nervous system

This piece was stimulated by a note published by

towards the end of March, 2025. Rebecca did some graduate research which was designed to explore issues related to the art practice of public school art teachers. She discovered that the teachers in her study didn’t have an art practice, because they were in no state to be able to have such a thing.In her note, she talks about her own situation of trying to keep a regular art practice amongst many other responsibilities:

I’m sure there are people that make art well under pressure in spurts, but I wonder if anyone buried by chronic stress can maintain a regular, burgeoning art practice. If this is you, and you need a random person on the internet to tell you you’re not lazy… let it be me. You’re not lazy. Your mind doesn’t make art. Your nervous system does. Trying to make art in long term fight or flight is like a fish trying to walk on land.

There’s been a lot of talk in recent years about trauma and the state of the nervous system, to the point that a backlash is already well-established, sometimes with good reason. But chronic stress is real, perhaps particularly for women. Thousands of people are boiling in their frog-pots1 and there doesn’t seem to be any end to this reality.

I’ve noticed a number of women writing here on Substack mentioning burnout, and there are presumably many more who write directly about this whose work I never see (I’ve muted this topic out of my feed). The writers I read mention burnout only in passing, which suggests that it’s widespread enough not to need any explanation.

Women talk about the relief that making art of all kinds has brought them, but for many of them their mother/support/career/caring responsibilities don’t diminish just because they realise that they need more creative space. The art that these women intuit is their lifeline back to themselves becomes one more thing that has to be scrabbled for, fitted in, contorted around. I wonder how many people end up like the dancer who told me that she booked a hall to rehearse her piece and ended up just lying on the floor for the whole of the time that she had paid for.

People manage, women persist, but the whole situation costs them sorely in terms of their health, and their creative spark. And then they feel bad, because they’re ‘not doing’ what they know is important. There are cultural undercurrents here, not only in terms of women’s expected roles and behaviours, but also in terms of how that creative spark manifests; how it operates, and what it needs.

Of course this is different for everyone. There’s no single way to manage your creative self and energy, everyone’s situation is unique, and women generally seem to be brilliant at making it happen in the midst of so many competing agendas. The day that I read

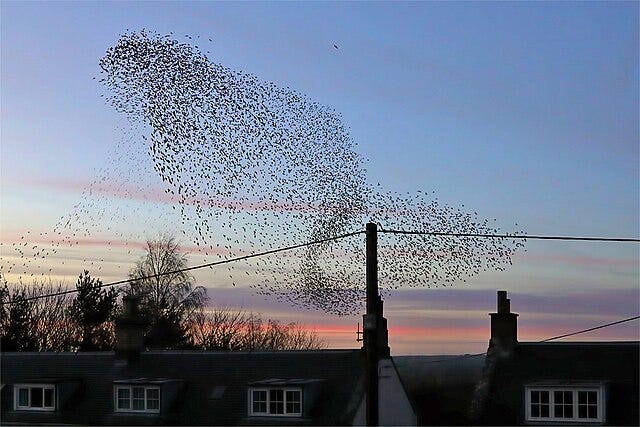

’s Note, however, I also read the quote below, and it got me thinking.Chi doesn’t move in straight lines – it spirals, coils and weaves like wind and water. When you force it, you block it. When you move with it, everything changes. [my italics]

whitetigerqigong, Threads, 24.03.2025

Euro/North American culture often recommends that we approach the world in a straight line kind of way; ‘Break your goals down into manageable chunks, be consistent every step of the way until you reach your target’, ‘Have you got a five year plan’?, ‘How are you going to achieve what you want in life if you don’t plan where you’re going?’. Straight lines are also the way that Euro/North American culture often chooses to approach research; ‘Show us what works in the classroom, so we can ensure that students will achieve desired outcomes.’; ‘Find out how adults learn so that we can make sure they pass the course’. It’s an older approach to science, a Newtonian world view – you hit the billiard ball, it moves along the flat surface in a straight line, it hits the next billiard ball. This way of thinking about the world is what feeds the search for cause and effect, for answers that explain why things happen.

It’s an approach that can work very well, but only for certain kinds of phenomena. If there’s an outbreak of food-poisoning and it turns out that everyone ate at the same restaurant on the same day at the same time, and the lettuces still in the kitchen at that restaurant are found to have salmonella, you have a result. But if you try to apply this way of thinking to human beings in social situations, you potentially have some very serious problems. There’s not really much similarity between ‘adult learners’, for example, if you stop standing back and looking across a hundred of them trying to find something that they all have in common, and instead move in close, allowing yourself to notice the myriad details of their observable, context-specific histories, motivations, and lives.

You can’t justify this kind of close-up analysis within the billiard ball approach. You’ll be told that ‘you can’t generalise from a single example’, or that ‘the exception proves the rule’. But the point is that if you’re interested in what is actually happening; in the observable facts of real-life examples which are not abstracted from the specific and constantly-changing nature of their multiple contexts, you won’t be trying to generalise in the first place, and you won’t be looking to find the deep structure of a universal ‘rule’.

This isn’t a vague or qualitative approach to research. It’s the implications of newer forms of scientific thinking which developed in the latter half of the 20th century, because the billiard ball approach itself eventually led to an inescapable realisation of its own limits. When it came to trying to understand both sub-atomic levels of reality and large, multiply-connected systems such as ecologies, weather, and human societies, straight line thinking just didn’t work at all. Chaos, complexity, dynamic systems, complex adaptive systems theories and many others, all developed new ways of understanding natural and social phenomena, now seen to be fluid, dynamic, multiply-connected and only partly-observable.

In many areas of life, though, the implications of these new ways of understanding and talking about dynamic expressions of life are still relatively unknown. I’m often struck when reading about creative processes, for example, how often well-meaning teachers and enthusiastic practitioner-advisers seem to be trying to encourage people to adopt a billiard-ball approach, in the sense of recommending an apparently simple, step by step plan of action. You’re exhorted to discipline yourself to ‘do something every day’, ‘start a sketchbook practice’, ‘join this supportive programme’, ‘set an intention’, ‘put in the hours’, ‘do the graft’. You’re presented daily, if you’re on social media, with an infinite number of ingenious ways designed to help you fool your resistance, erase your exhaustion, annihilate your confusion, and get you onto the straight and narrow of, apparently, making art products most of the time. Or at the very least, making art on a regular, non-negotiable basis.

I can’t speak for anyone else, but life trained me to be incredibly good at forcing myself to do things that I had no desire to do. I had to eat, so I took the job. I had to keep the job, so I met the deadlines. I needed to rest, but I kept going. The demands of the timetable meant that I did produce the result on time. There was no question of not doing it, so I found a way through. I learnt that the way to avoid the stress of approaching deadlines was to just, well, work most of the time. There was never enough time to do the job properly, but if I spent enough time examining the thing, reading, thinking about it, I could make something good enough and not feel stressed about the whole process, at least at the level of my by-now-somewhat-dissociated awareness.

This straight-line, pushing-through approach to working, and therefore to my life, was not natural to me as a biological system. I became a master of override, learning how to nourish my cells with good food, move my stress hormones with exercise, and not work after 6pm. It turned out though, despite all these clever tricks, that my life-energy was not going to tolerate this behaviour forever. Eventually, the natural forces that wanted to ebb and flow, advance and retreat, spiral and weave like wind and water, tides and rain, took over. Gently fogging out my brain and asking me to lie down, they began to speak to me in a new language, which ultimately I was compelled to listen to. As I eased into this new space, my art slowly began to reappear, after decades of absence.

In the years that followed, I had a lot of unlearning to do. Here I was, finally doing what my almost-forgotten heart had desired for half a lifetime, but the only way I knew to approach anything was, you guessed it, to do it all the time. Now there was no deadline, no externally-driven imperative, and a new connection to something that delighted me endlessly. I’ve written before about my youthful vision of the inflamed artist flinging paint onto their enormous canvas, and the many years it took for me to slowly learn that this was not the only way to go about doing creative work.

Chi doesn’t move in straight lines – it spirals, coils and weaves like wind and water. When you force it, you block it. When you move with it, everything changes.

I’m still learning how to let go of the survival-push that kept me going through all of my life’s demands and challenges. My Chi, my life-force, is powerful and persistent, and I’ve often felt at a loss as to know how to let my creative energies move in ways that don’t strain my biology. The only thing I know for sure is that if I try to discipline, override, organise, plan, set intentions, put myself on programmes - basically anything that has been invented by a human mind, mine or another’s - I will be going against what’s trying to naturally spiral, coil and weave from the source of my being.

I’ve had to accept periods of silence. Times when nothing moves, and nothing is made; and to know that these periods are not just ok, but essential to sustainable art-making. Not only in the sense of ‘taking a break’, but in terms of the art itself, that art can’t breathe and grow without space.

Art can’t breath and grow without space.

I’ve learnt that equating not-making with failure or loss is not only wrong, but that it can actually gradually erode both my art and my nervous system, creating tension and stress. For me, at least, when I force it, I block it, but when I move with it, everything changes.

For it is not slowness that tires,

It’s the constant sense of urgency.

Some things cannot be forced.

Sleep, trust, ripe fruit, forgiveness.

And yet, we try.

We want to grasp everything, understand everything, transform everything - right now.

But what’s alive doesn’t respond to command.

It responds to attention.

To silent fidelity.

To the space left empty.

Like dew on grass in the morning.

Words of Taoism, 12th May, 2025

An image that’s been around for decades about frogs and pans of boiling water. If you drop a frog in a pan of boiling water, the story goes, it will jump out, but if you put it in warm water and slowly heat it up from below, it apparently won’t notice and will end up being cooked.

I'm so enormously glad I stumbled across this today. I'm going reread it every day this week as I try to process what is feeling more and more like creative burn out. I know, I deeply deeply know, that I need to live my life more in flow with the Tao, with chi, and I'm not doing it. Something needs to change. Thank you so much for this.

I totally feel the paradox of billiard ball approach. For highly sensitives and intuitives, our perceptions is never linear. Our mind is a dynamic network with multiple nodes activated.

I was blindfolded by those goal-setting, 30-day challenge, goal breakdown methods for so long. Yet to realise our artist's growth is never hitting billiard balls.