Chinese landscapes and the ineffable Tao

Not responding to, but actually summoning reality...

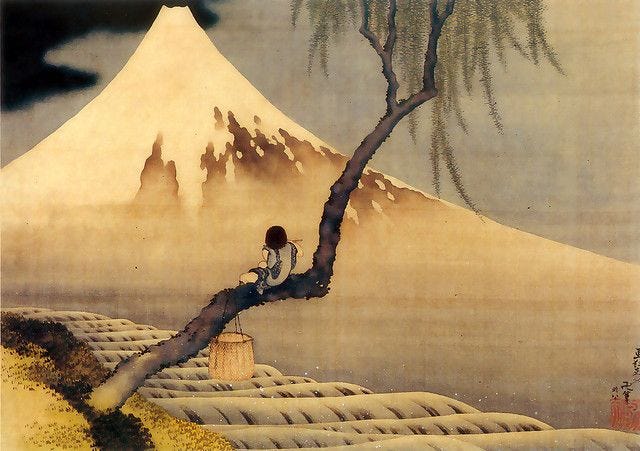

At some point when I was living in Italy, painting landscapes and flowers and wondering why nothing felt right, I started to look at Chinese landscape painting. I had no idea how to respond, so for a while I just copied the paintings, making big charcoal drawings, trying to interact with the spirit of them. My hand followed their mountains and their rivers, their trees and their clouds, feeling their energy. I read that the paintings were in service to the idea of the Tao, an idea I immediately loved; it was the mystery and power of the world, the physics of clouds and rain, the movement of wind, without the need for anything supernatural or godly.

Around this time an old art school friend, now making it big in London and New York, came to stay with me. She was five years older than me and the epitome of my fantasy of the artist who appeared to ‘know what she was doing’. I remember three things about her visit. First, she told me that I was more dedicated to art than most of the people she encountered on the world art stage. I didn’t know what to make of that. I think it probably confirmed my sense that the art world was a bonkers place and that there would never be any place for me there.

She also told me that if I was going to do this kind of work it was vital that I had a community of other people doing the same thing. This I did not have, and I had no idea how to go looking for it amongst the hills of Umbria. I was used to working things out on my own, and I just assumed that the artist’s life was a solitary one.

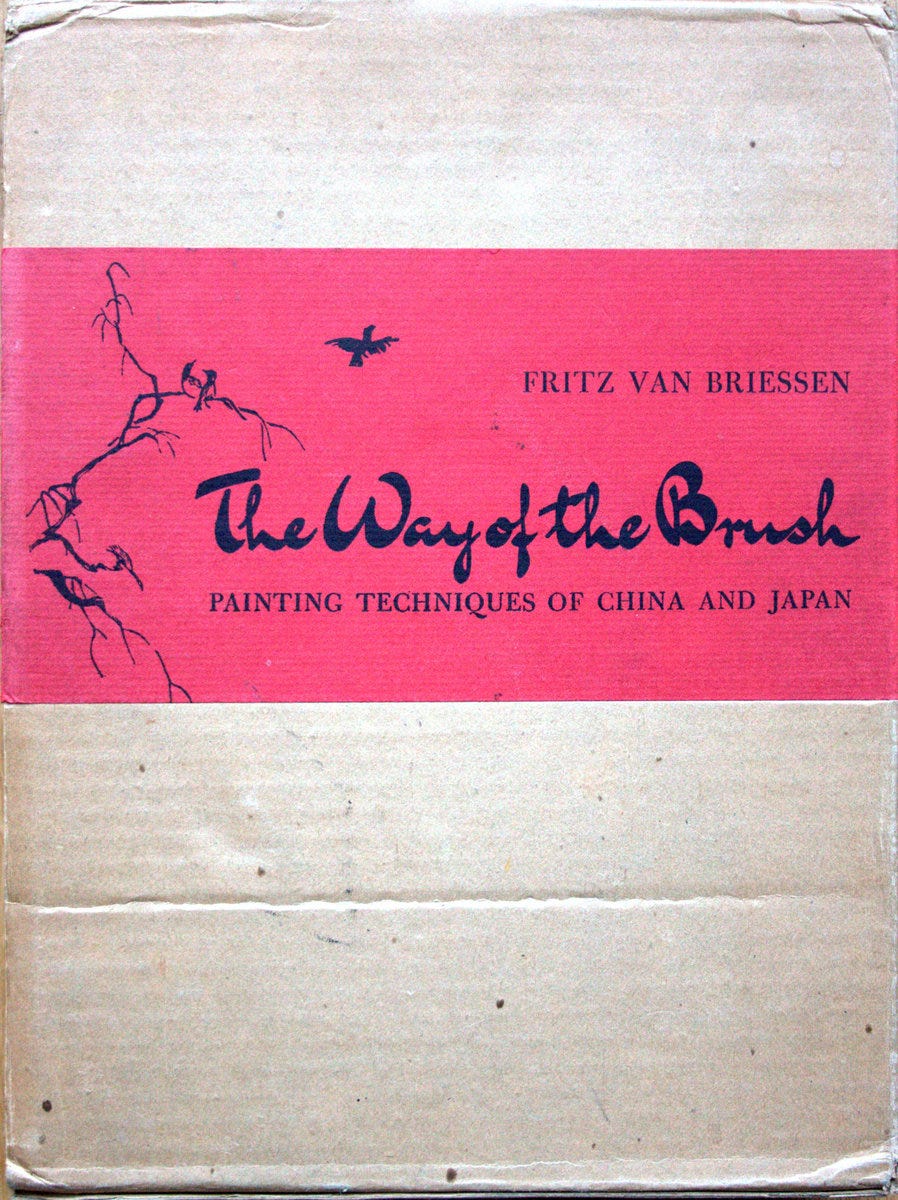

After she left, she sent me a book called ‘The Way of the Brush; Painting Techniques of China and Japan’. I don’t know if this is what started my interest in Chinese painting, or whether she gave it to me because she knew about my drawings, but in that book I found a key.

The first part of chapter one was called ‘Painting and magic’. I didn’t really take in the magic part, but the stories I found there have stayed with me through the years.

Ku K’ai-chih one day decided to paint a dragon on the wall of his house. He guided his brush with full confidence, and after a while the dragon was finished except for its eyes. Suddenly the master’s courage failed him. He simply did not dare to paint those eyes. When, many months later, he at last felt brave enough, he groped for his brush and with swift strokes dashed in the eye and pupil. Within an instant the dragon broke into loud roaring and flew away, leaving a trace of fire and smoke.

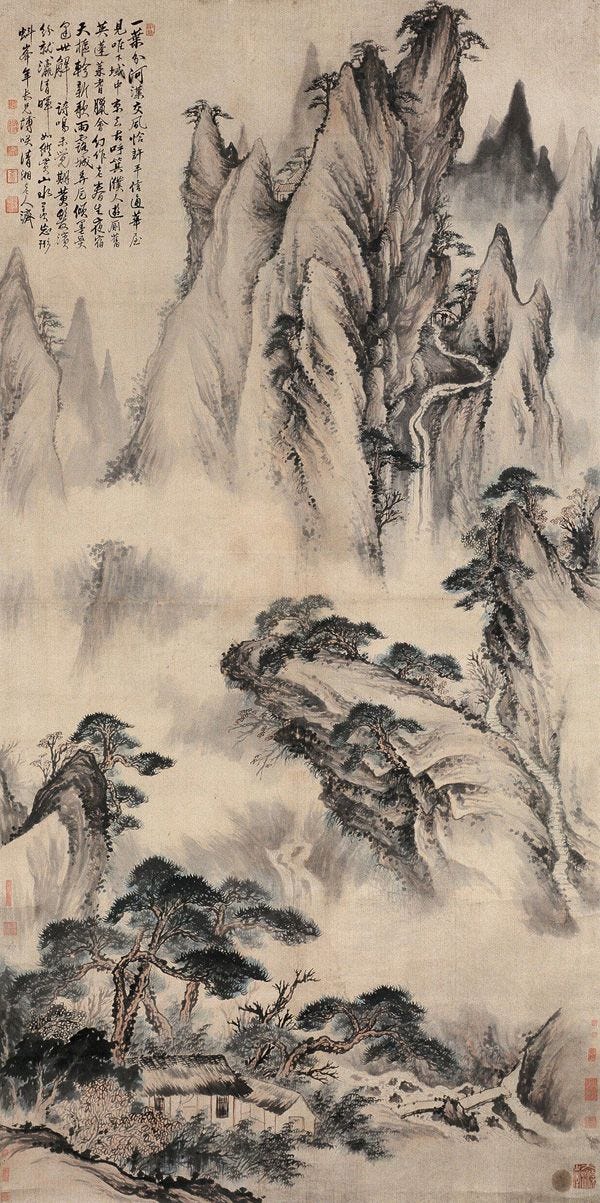

Two painters, Li Ssu-hsun and Wu Tao-tzu, were commissioned by the emperor to produce paintings showing the thousand miles of the Kialing river. Li worked furiously on sketches and notes while Wu wandered around admiring the beauty and wildness of the country along the great river. Then both artists returned to the capital. Li, the realist, set to work with help of his sketches to paint the entire length of the river on the palace walls. But Wu haunted the inns, drank wine, and enjoyed the singing girls, doing no work at all. Within the palace the courtiers began to get worried, but outside, Wu was perfectly happy and without a care. There were only two days left until the time limit set by the emperor would expire. Li’s painting had already taken glorious shape when Wu finally appeared at the palace and started work. With tremendous zest and great sweeping strokes, he began to the throw the bristling spirit of the Kialing onto the walls. Mountains soared into the air on the wings of his brush, torrents roared around the bends in the cliffs, and the solitary footsteps of pilgrims clattered hollowly over the fragile bridges. In two days, Wu had conjured up a masterpiece a hundred times worthier than Li’s splendid craft.

This was something. Painting had power. Painting could manipulate living creatures, transmute materials; it could reach in to a space between the worlds, create and take life, play with the deep energies of the universe. Here it was, maybe. The real purpose of making images, nothing to do with galleries, or investment, or carefully arranged still life.

Some years later, I was reading a book by Simon Leys, where he made some clear comparisons between Chinese painting and painting in my own culture. I copied it all down in my notebook.

Painting is an act of creation, not of imitation. In the West, both classical antiquity and Renaissance culture considered that art possessed an essentially illusionist nature.... While Western artists applied their ingenuity to deceive the perceptions of the spectator, presenting him with skilful fictions, for a Chinese painter, the measure of success was not determined by his ability to fake reality but by his capacity to summon reality.

... not the painting’s illusionist power, but its efficient power – it achieved an actual grasp over reality, exerting a kind of ‘operative’ power.

... The relation between the painted landscape and the natural landscape is not based on imitation or representation; painting is not a symbol of the world, but proof of its actual presence.

... The purpose of painting is not to describe the appearances of reality, but to manifest its truth.

And finally:

If a painter’s works ‘lack breath’, all the other technical qualities they may present will remain useless. Conversely, if they are possessed of such inner circulation, they may even afford to be technically clumsy, no formal defect can affect their essential quality.

I’ve carried these ideas with me my whole life, but these days I would be careful about such easy comparisons. I imagine there’s a counter argument which would say, ‘Oh, but we have magic and mystery too, look at Blake, at Dali, De Chirico; look at the icons of the Holy Virgin, and pentangles in Wicca ...’. But it didn’t feel the same to me. Most of the ideas I had been exposed to about magic were associated with the spirit world and supernatural powers that I didn’t believe in, or with Christianity, which I was horrified by.

I can see that someone might argue that Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘Face of an Angel’ goes beyond simply representing the outward forms of objects in the world; that it’s a deeply subtle expression of life force, a capturing of energy and character. But for me at that point, now 26, quietly drawing enormous pastel garlic cloves and fake Chinese landscapes in my farmhouse in Umbria, subtleties like this were yet to come. I hadn’t been able to find the life I was interested in in most of the art I had seen, and I was convinced that there must be other ways, other meanings, other purposes.

I never considered my interest in ‘the power of images’ to be about magic; the power I wanted to draw attention to was the mystery of all living things webbed together across the planet, the miracle of our being here at all. I was beginning to feel that my job was not to focus on exactitude of light and shade, or believability of line and form, but somehow through my painting to say to a viewer, ‘Look, look again, do you see it?’

I remember one day looking into the heart of a cypress tree, just below where the green branches began, deep into its thick maze of trunks and darkness. I felt something, as I was thinking about shades of brown and black, about the texture of different kinds of paint, about how to respond. It was another moment that fixed itself in my memory, like the lichen wave, like the tradescantia. Something was speaking to me, but its voice was still faint, its language unknown.

All I knew was that I wanted to feel something when I looked at a painting, to be shocked, astonished, moved; somewhere I knew that art could do this, and I was determined to find out how, and why.

Your writing is so moving. I ended up here from there, the more recent post with the link.

Now I will go back there from here.

So it has been your writing which transported me.

The dark place below the branches, but above the ground leaves us in mystery. So too, often do your works. There is a certain combination, a dark deep hue and the figures emerge dancing as if from that dark place beneath the trees, there has been a party going on I missed.

It always makes me with I had been there. So that is where I am going next.

I appreciate your coming here enormously. These early articles contain so much for me, I feel like I want anyone who reads later things to start here, to understand these early intimations and connections, and hear about the huge current of life that I feel connected to. It's all so much more than 'here's what I made in 2018'..... Thank you for engaging.