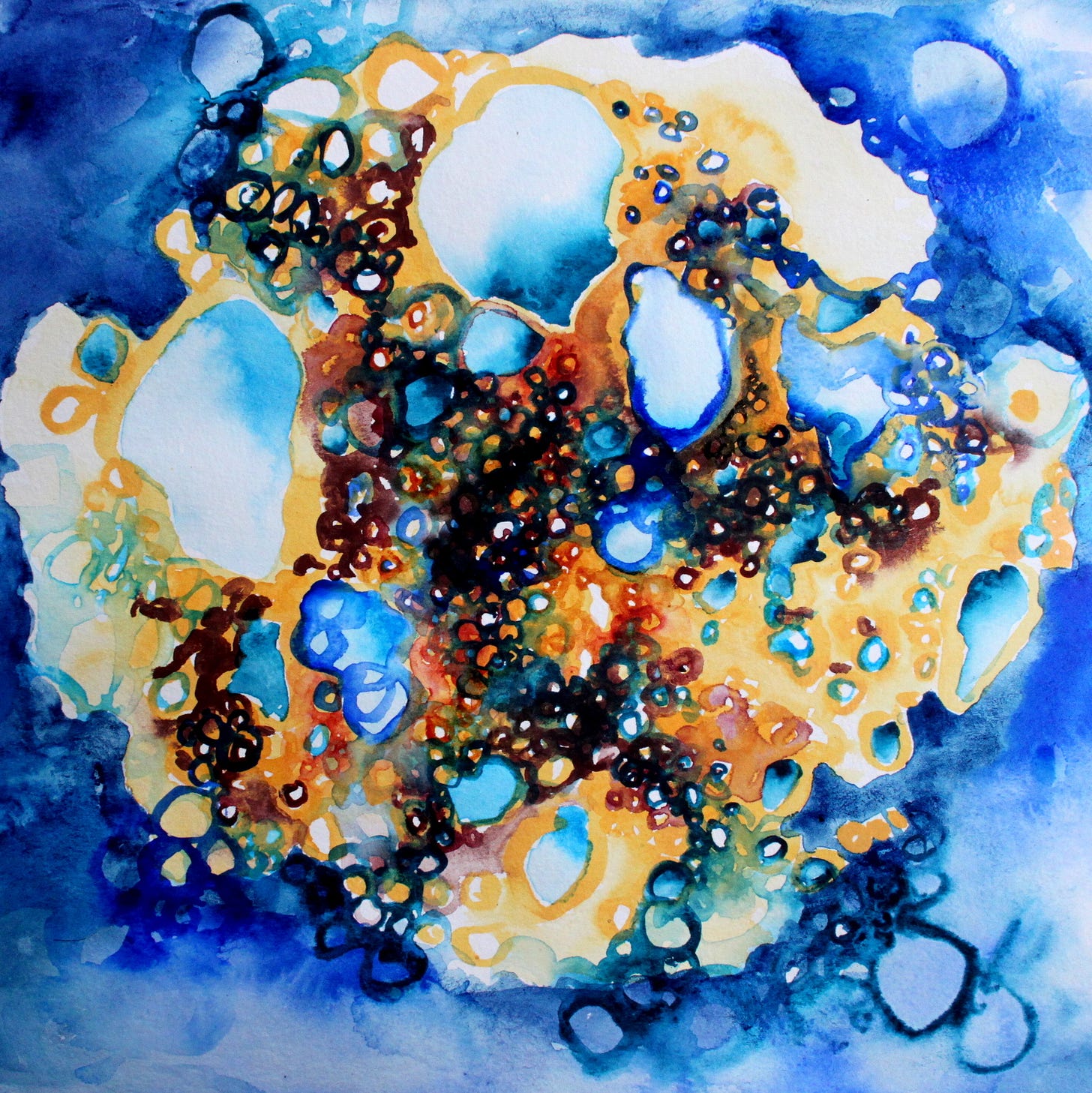

The cosmic poppadum

India, shapes and colours

I ended Dancing Cells talking about the unexpected opportunity of a show, which came up in September 2013. But before I talk about that, I need to backtrack a little to the year before.

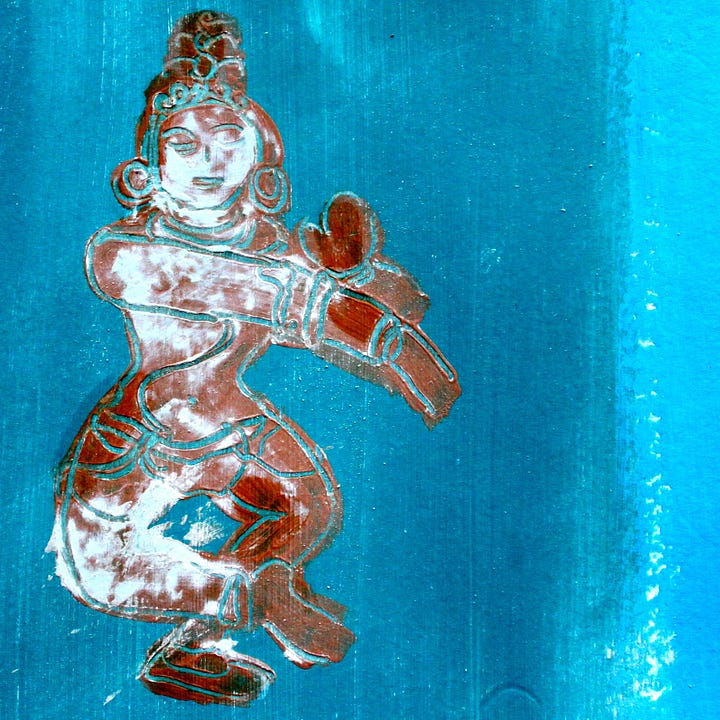

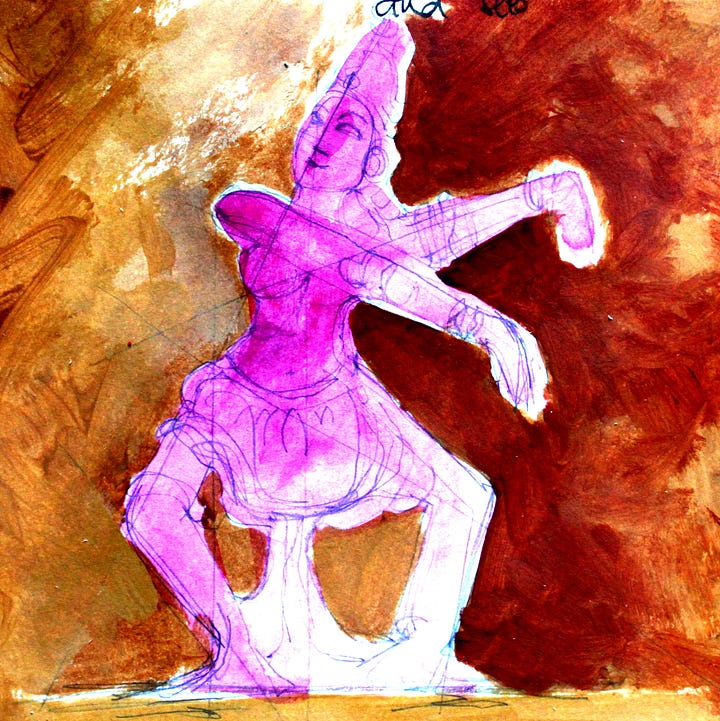

Some time in 2012, in the middle of experimenting with large fields of acrylic paint, something strange happened. The most famous image from the Ajanta cave paintings, of Avalokitesvara, mysteriously appeared on a piece of plain paper, along with some dancers.

I was working with running paint, messing up grounds, exploring texture and effects. The drawing was totally out of character, not at all what I was doing. Before I knew it, there were statues sitting on the painted fields, turning my grounds into galaxies.

The statues intrigued me and troubled me at the same time. What the hell were they doing there, with their perfect forms, their already-in-the-world existence, art-forms from another time and place? It wasn’t surprising, given how long I had spent looking at such figures during my degree, and the fact that I had written a dissertation on the embodiment of god in these exact forms. But, I was in my fractals and my paint, not thinking about them at all, I had no intention of inviting them in. And once they were sitting in the cosmic space that my paint experiments became after they appeared, I felt a bit disturbed. It was all too vast, and too difficult.

A month or so later I started playing with small images of dancers carved into the doorways of temple compounds. Some of them were missing hands and feet, some were chunky and unfinished, but their energy compelled me. Simply copying them was out of the question - nothing could be as beautifully imperfect as the original - so I had to interpret in some way. I tried to get the feel of their movement with my direct, flowing line (no pencil drawing beforehand, so that wonkiness would appear).

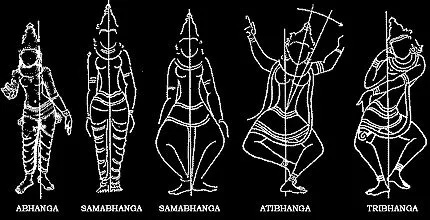

I went back to my books, reading about the importance of specific shapes and proportions1, and was reminded of the concept of tribhanga. The last image on the right below, the tribhanga pose, is when the body bends in three different angles; head and shoulders one way, hips another, with the third angle at the knees.

This is one of the ways that Indian sculptures portray such amazing life and movement.

The figures rose up from my unconscious around the time that I started planning a trip to Kerala, South India. It was my first trip to India since 1994. I had no plans, I just needed to go.

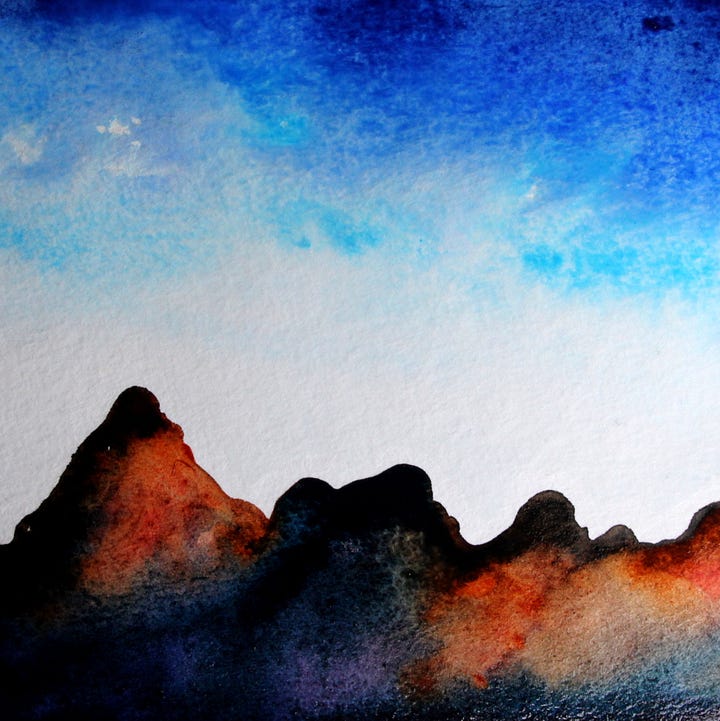

When I arrived I headed straight for the mountains close to Trivandrum, to Shunil’s wonderful Bioveda hill resort.

I began making fractal-type paintings of poppadums and bitter gourds, watery mountains.

Behind where we were staying was a huge rock with a small temple at the top. Every day we would see people sweating up its sheer surface to make offerings.

Then we went on to Kochi, and beyond.

Colour, everywhere. Not only saris, dazzling combinations of unexpected patterns and colours, but also walls, flat fields of colour unlike anything anywhere else on earth. They flooded my imagination, coming out a few months later as the coloured grounds of the later Wild Life paintings.

I’ll tell you about Wild Life next time, and why it had to include live sandpainting…

In the case of the main image in the temple, images must conform to specific proportions and certain idealised standards of beauty in order to attract God.

These are beautiful! And anzing to hear how they just came to be, specially Avalokiteshvara. Also, thank you for the education on the pasture of statues.

This is so interesting. I am fascinated because the appearance of images happens to me too. And on staying with the image some form of meaning occurs which takes me deeper into my understanding. Thank you!