Teaching and the Chinese dragon

On classrooms, educational theory, and falling in love with Complexity

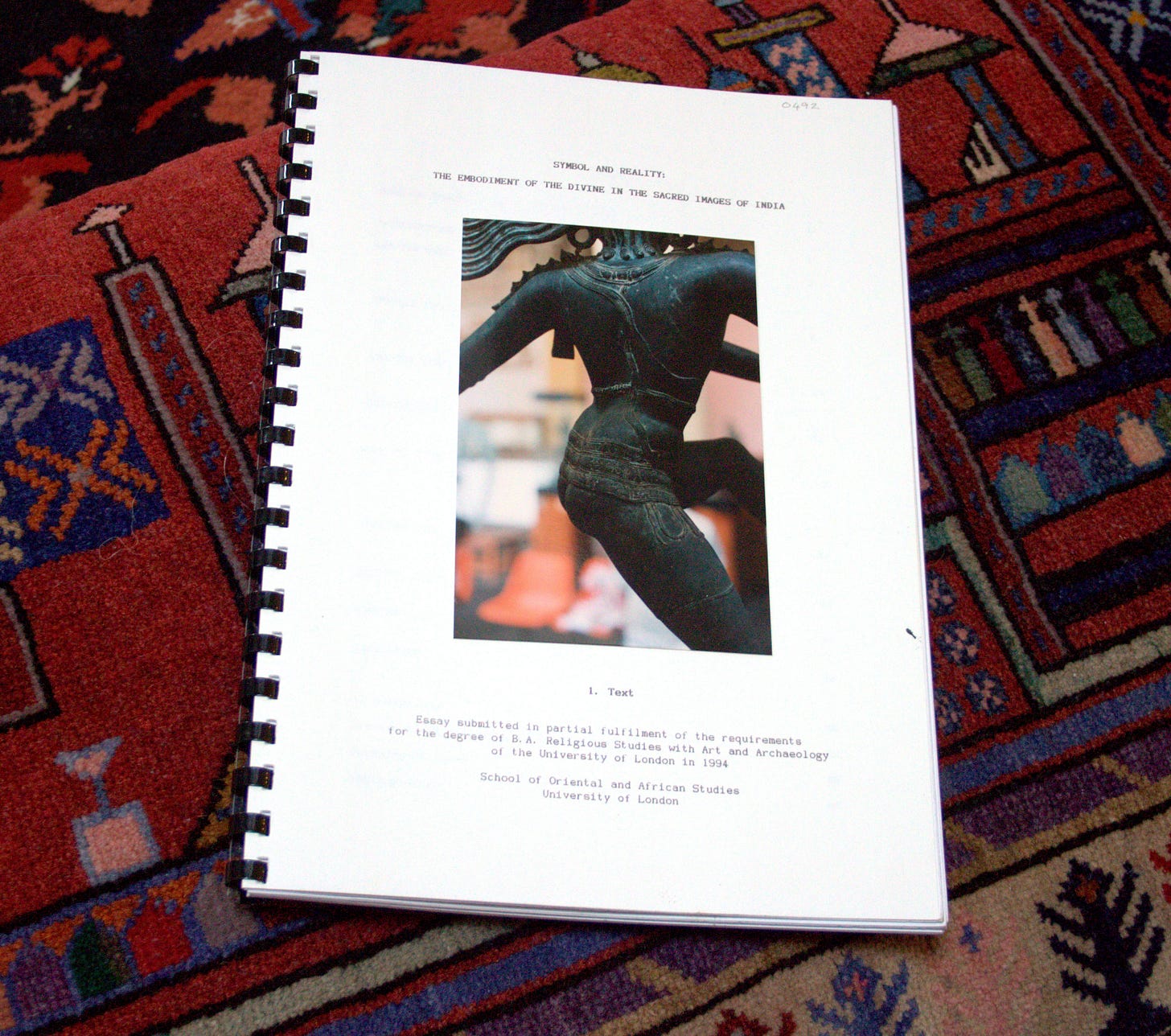

In my previous piece, I followed my path into the formal study of Indian art, tracking how my interest in the power of images ended up with me interviewing worshippers, temple builders and scholars in Tamil Nadu, South India, for my final dissertation. It was a three year journey of love, which like my previous journey of love (teaching Tibetan refugees in Himachal Pradesh), eventually had to come to an end.

What does an art pilgrim do at this point? I considered doing a PhD, but that would have involved intense study of at least one South Indian language, and the next few years spent travelling and researching in India. I was a bit tired of dust and dirt and lonely research. I looked at the academic posts which further study might make possible; there were about six of them in the world, and most of these were already taken by young professors who were not going to vacate any time soon. As before, I’d love to be able to say that at this point I took a nice long break, and then came up with a plan for using my Indian art studies in the world, improving upon my previously limited employment possibilities and experience as an English teacher.

But no, I went right back to short-term English teaching, six hours a day, five days a week; my default survival strategy. After all of my intellectual and travelling adventures though I was soon horrified by the repetition and drudgery of it. I saw an advertisement in the paper for a Masters in Adult Education at the Institute of Education, London University, and immediately enrolled. It seemed perfect. Ten years of experience as a teacher of adults, then three years full-time study as a student in the higher education system; I had experienced things from both sides, and perhaps I would be able to make it interesting.

Teaching English as a foreign language gets a bad press, but it’s actually a very creative profession, and many of the people who do it are artists, writers and musicians. It’s a ticket to a life of cultural exploration that goes beyond tourism; you live in interesting places, you work with the people who live there, you learn their languages, and their ways of thinking and being.

I was lucky to have been trained and employed by an unusually vibrant and creative school. They had an in-house trainer who gave us weekly inspiration on how to approach the freedom of English teaching in such a way that we eventually learned how to connect with ‘a source of ideas that would never run dry’. I learned how to make a whole lesson out of the first three things that the students said when they came into the room; how to take personal sentences they wrote about things that were important to them and turn them into a grammar lesson; how to bring in images and get groups writing stories and plays; how to cut up articles on current affairs and turn them into puzzles. As long as the students were interacting, you could pretty much do anything you wanted; with the added spice that as they were paying, you had to keep them interested or they would complain. It was a lot more work than ‘open the book at page 11’, but it made every class unique and exciting and full of unexpected surprises.

Now, in the Masters in Education, I felt like I had woken up in somebody else’s life. Politics, policy, sociology, psychology; I couldn’t have cared less. But playtime was over. I stayed. I was amazed to be faced by teachers standing at the front of rows of static desks, droning their way through endless bullet points on unillustrated overhead projector slides. When I started reading educational theory I was hit by a raft of ‘models of adult learning’, every one of which appalled me, with their neat circles and pyramids, their straight arrows and lines, their identifiable characteristics of ‘the adult learner’. Everyone knew that adults were diverse, not a category, and everyone knew that there was no such thing as ‘what worked’ in a classroom, right? Hadn’t we all tried to use the same lesson plan with more than one class and had it fail spectacularly? We all knew that working with groups of adults was a matter of orchestrating a mysterious energy; that any class on given day was a unique animal, which had to be felt, responded to, sometimes tamed, sometimes applauded, sometimes roused out of apathy... didn’t we?

It seemed not. This was academia, and there were a lot of vested interests in Education. Policy-makers and heads of schools wanted knowledge, they wanted universally-applicable models that would guarantee ‘successful outcomes’, as wider political and outcomes-based agendas pressed in upon them. I wasn’t having any of it. I devised a research project which interviewed post-graduate students about their ‘learning processes’ within the institution, and contrasted what they told me with all the neat and tidy models and categories. This proved to be a smart move. Within a year I was in an academic post at a university, where there was massive scope for furthering my critique of all that contrived, pesky neatness.

As a researcher wanting to critique models of Higher Education learning, I was always looking for some kind of theory or approach which would let me make my arguments about difference, the specificity of particular contexts, the multiple factors at play in the relationship between teachers and students in a group. But I couldn’t find any existing perspectives that would let me do this. Until one day, I was holiday, and I started reading James Gleick’s popular science book on Chaos. For the first time in all my turgid reading of educational philosophy, post-modern thinkers, sociological perspectives, I got excited. Really excited. Here it was, like virgin snow. Not being applied to education or even social science; a sparkling new way of thinking and talking about the limits of knowledge, the inherent unknowability of many aspects of biological and physical processes, the unexpected and unpredictable realities of things-in-the-world appearing without any identifiable cause.

Complexity theories highlighted, rather than ignored, all the things that were so difficult for traditional research models to accommodate: unpredictability, context-specificity, non-linear processes, multiple connections at a local level, de-centred processes that were too fast and too connected to ever be able to observe. It was a way of thinking that accepted the existence of all kinds of unknown things, which were accepted to be operating and having effects, but without the expectation of being able to pin them down or explain them. Traditional models said, ‘One day we’ll have done enough research to be able to fully understand all this’. Complexity said, ‘There’s no way we can ever track all of this, and it’s not just because we don’t have clever enough computers, unknowability is just part of the world’.

Many educational theories had basically been invented and then applied to the world, as a ‘lens’ that might or might not help understanding of what could be observed to be happening in real educational contexts. It was value-based guess-work, at best. Complexity had maths, it was a model from the ‘new sciences’ (ie theories that went beyond Newtonian mechanics, such as quantum theory) which was being used to describe all kinds of observable phenomena in the natural and human world: the behaviour of ant colonies, bee hives, slime moulds, the evolution of neighbourhoods in cities, patterns of crime, human uses of architectural structure, psychological development.

The 50s and 60s had seen very individualistic models of ‘adults as learners’ appear in cognitive psychology, ‘brain on a stick’ models which took no account of social and cultural contexts. The reaction to this in sociology in later decades had been to prioritise social and cultural forces as the fundamental mechanisms which formed people in particular ways, seeing them, in a sense, as ‘products’ of things such as class, gender, and ethnicity. This seemed to me to be going from one extreme to another; first, there was individual with no context, then there was a context with no individual. The later sociological reaction seemed to have wiped out any possibility of understanding people as unique individuals who could, at the same time, also be created by, even largely made up of, much larger social and cultural forces or energies. The problem was how research could accommodate this radical, context-specific, reality.

Complexity provided a way of starting to talk about all of this untrackable unknownability in the context of education . If you thought of people as individual, open, dynamic systems (Carmen, Fred, Amira), embedded within larger dynamic systems and histories (culture, convention, belief systems, social class, educational structures), and containing smaller dynamic systems and histories (individual initial conditions, genes, trauma history, predispositions, adaptive patterns), all interwoven on multiple levels, and interacting with each other in myriad, very fast ways (periodically giving rise to emergence, but that will have to wait...), you began to have a sense of what was going on in real flesh and time. I say a sense, not a clear picture, and certainly not something that you could generalise out to fit a policy agenda.

Complexity was beautiful to me because ‘too-fast-to-see-or-track’, and ‘too-connected-to-unravel-causality’1 were accepted as key elements within the overall framework. Someone once asked at a conference whether complexity was ‘an unclear picture of something clear’, or ‘a clear picture of something blurry’. The intrinsic unknowability of many of the processes of life were taken as read and celebrated.

I spent many years twisting my brain into pretzels and cones and helter-skelters, trying to work out how to use this way of thinking to analyse my data, and to argue for what I knew from experience to be the uniqueness of each individual student, of every group of adults in a classroom at any particular moment in time.

Writing this now, I see that conducting the live processes of the mysterious, every-day-different energies of a group of adults in a classroom felt to me like the Chinese landscape painters dancing with the energies of the mountains and the rushing torrents of the great rivers. You can research and learn and study all that there is to be known about people and classrooms, rivers and wind, but on the day that you teach or pick up your brush, you can only hope and pray that your antennae will be functioning, and that you will somehow manage to ride the lifeforce that is guaranteed to arrive in unexpected ways, each and every time.

Complexity theories don’t just say, ‘It’s all very complex’. They recognise causality, they just don’t expect it to be linear or explainable.

Thank you 🙏🏽, I am two post into your Substack here and I wanted to ask, thank you for your thoughts and sharing this type of work. I did a the grad school thing and taught college English and had a tough time with the whole thing (I’m doing much better now).

What came up for me during this read from a zen Buddhist perspective is, What is the direct human experience of complexity? I use to think complexity was overwhelming— coming from that mind that loves taxonomies. But, now, I am learning to accept and love the unknowable, and allow complexity to arise from this thing called “me.”