I’m taking a pause now, looking back at 20 weeks of publishing here on Substack. I started with myself at the age of 16, turning up at the Berkshire College of Art, full of hope and ready to learn about art. I arrived at last week’s piece some forty years later, marvelling at the appearance of strange, other-than-human creatures which were a composite of Indian dancers, peacocks, and various other birds.

Throughout the last fifteen years that I’ve been back painting, I think I’ve often felt that I should be understanding my direction, moving towards knowing. That breadcrumb trail, which I thought was leading somewhere. Just carry on, I said to myself, and it will become clear. Soon you will know. You’ll have your vision, and finally you’ll be able to relax a little, loving its lines, soaking up its colour, laughing with its forms.

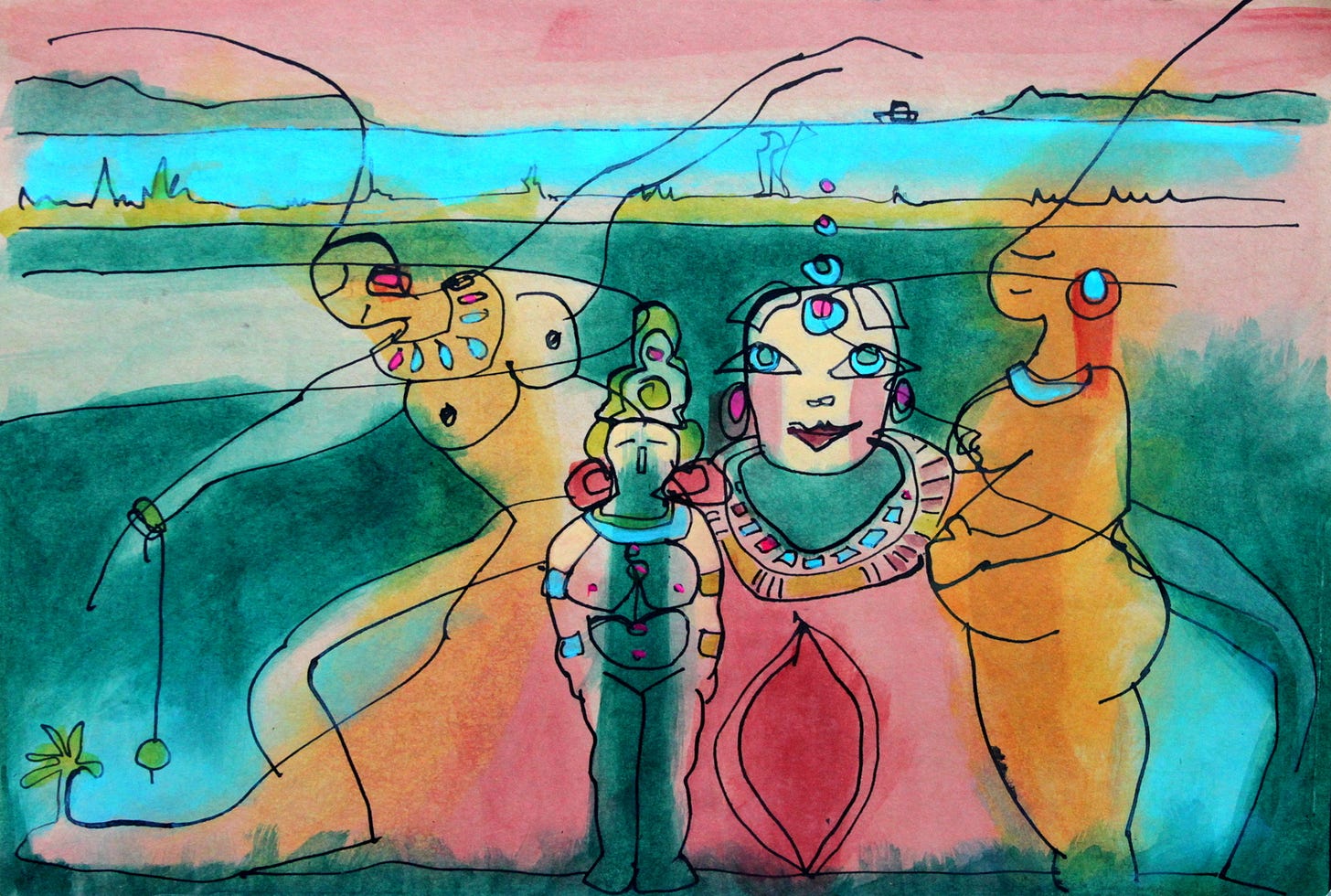

Life herself tried to teach me. The lichen wave looked me straight in the eye, the Himalayan rhododendron trees sang their song. India tried to teach me too. The movement of breath through a dancing torso showed me life, over and over again; the murals of Mattancherry palace showed me a teeming fecundity that was quite different to any life painting I had ever seen.

But for some reason, even as I followed my instinct for discovery and improvisation, not seeking to fix anything or create a style, it was often hard for me to see that my wild experimental path was itself what I had always been waiting for; the thing that I had hoped would one day spontaneously appear.

The ‘free line’ was a thread, a thin rope thrown to me from the depths of the living world. It appeared very early on, when I was living in a farmhouse in Italy; a doodle that came from nowhere. It held everything, though I didn’t know it at the time.

It was a line of no planning, emerging into forms that appeared out of the void; a strangely insistent human, raw and bloody, with an umbilical cord that shared its life force with a tree, and the grass below its feet.

The line came again in the Himalayas, as I stood in the rhododendron forest. This time, living as I was surrounded by endless beauty and fascination, there was no stopping it. I would just sit down in front of something and start, and the life buzzing around me would flow down into my pencil, temporarily erasing me.

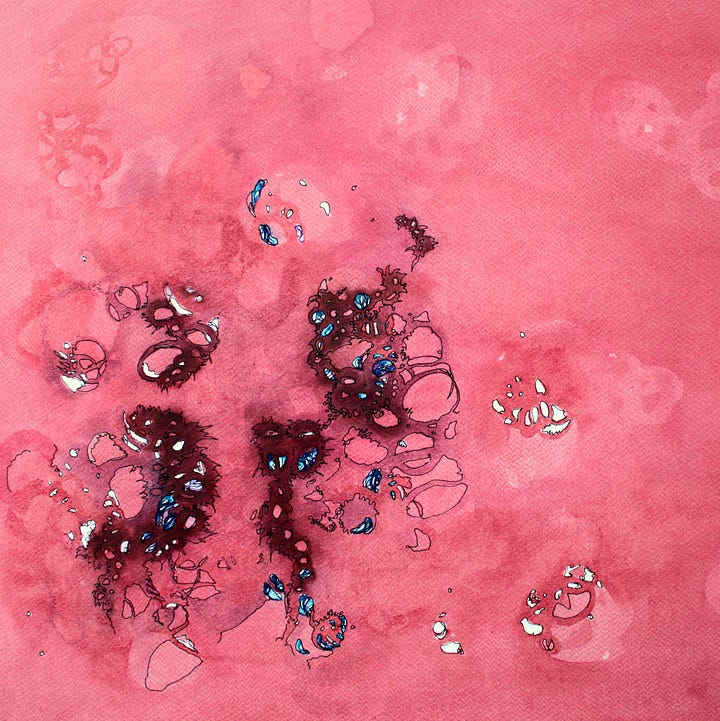

I’ve previously told the story of how the line then became lost, and how eventually, decades later, a split-open cabbage appeared to show me the way. This time the line was more hesitant, appearing first as an outline of watery fractals, before eventually finding a strong form of its own.

Then I went to see the sculptures in South India. It took nine months for a free line response to them to emerge.

Simon Leys talks about Chinese landscape painters ‘not representing but summoning reality’. The free line feels like that to me. I’m not using the line to consciously create an illusion, to try to capture a likeness of what I see in the world around me. The line, when it manages to get free, is life moving across the page, in real time and space. It’s the same force that animates the curve of the plant stem, that fills a sleeping cat with breath, using my cells to dance.

The free line can only be an improvisation. It usually appears, and certainly appears in its most compelling form, when I’ve been tricked into looking the other way. I know now that this is why this whole process has at times felt so hopelessly frustrating and unsatisfying. How can I want an image to surprise me, have its own life… and at the same time be something that I recognise, that I like and approve of?

The free line says imperfection, wonkiness, perhaps lack of skill. It says folk art, heart, human-ness. It says dreams and unconscious, feeling instead of concept; it says see me whole, not manufactured for your approval. It rejects art world norms, colonialism, cultural superiority; it says no to Darwinian ideas of ‘cultural evolution’.

It’s taken me a long time to find out that, for me, making art is a response to the world, not an internal welling up from a place of certainty. That image of the lone artist, who to my younger self always looked so self-assured as they sprayed paint around in a fit of passion (hello Francis Bacon), is a particular cultural model, and it’s not the only way.

I was never required to be driven by an internally-generated passion – all I had to do was open to the world, receive it, and start a conversation. My wonder and awe at the magnificence of life; the way that I felt the vastness of the sky enter into my bones every time I stepped outside, was not supposed to stop me in my tracks. But with no education to map a path, no mentors to guide me, feeling like an alien in my own environment, I had few tools with which to work this out on my own.

My lack of educational and cultural rails was a massive impediment, but it was also a liberation. It took decades for me to shake off the imperatives that my art school experiences hobbled me with, but in the end I did get rid of them. And then I was free. Lost, angsting, confused, but free.

‘Creativity is an opening, not a focussing’. I don’t know who said this, but it’s been on my wall for years, a constant reminder. An opening to energies beyond my own thoughts and intentions, my half-understood desires; energies that I can feel through the different levels of my awareness, but which can’t be approached directly.

I refuse to call myself a folk artist. I’m an image-maker who insists that she makes paintings, that she makes art; with my free line in open revolt against intellectual cleverness and hierarchies of skill.

We don't always see the beginning at the start. And yet it takes us all over the place in many glorious, messy ways. Here's to your free line image-making!💚

I have really enjoyed your posts and hope there will be more. I try to remember that to approach art making is an invocation … maybe you feel that too?