Eye to eye: power manifests in stone

I find out that Indian images also summon reality, but not of the Chinese kind

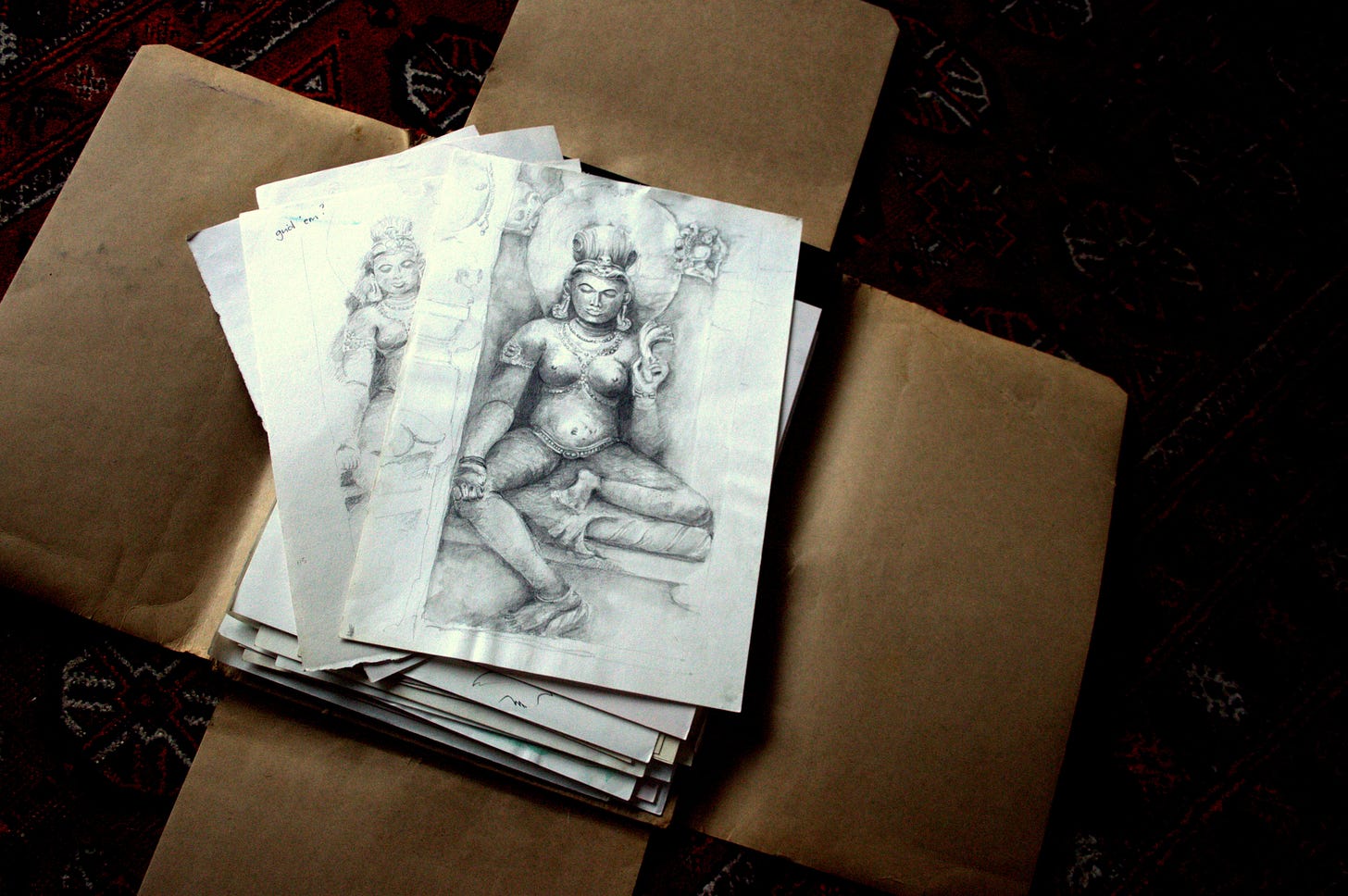

When I was looking at the tonal drawings from my final stay amongst the Tibetans in North India, I came across this one of an Indian carved image. I don’t know why I decided to study this sculpture so carefully, I had no conscious sense of being interested in such images. But somehow I ended up in front of this unknown figure, from an unknown religion, trying to feel it. I would have known that the image had been made for a specific purpose, that it wasn’t just an individual artist ‘expressing themselves’. I couldn’t put my finger on what I wanted, but there was something unknown there, something that I wanted to understand.

There are three other drawings that came after this one, which show that I was trying to break out from observational accuracy and find some form of free line response instead; perhaps because an unconscious part of my mind intuited that something to do with living energy was connected to this apparently inert stone. But all of that was to come later.

I got into Edinburgh University at the age of 33 through a secret pathway known as the Special Admissions Procedure. After two days of written tests, essays and interviews, all of my educational deficits were mysteriously erased. I was in, suddenly admitted to an institution that I had never imagined would ever be part of my life. I remember walking into the dark Victorian building half way up the Mound in Edinburgh; New College, home of Religious Studies, towering over the city like a great black wedding cake. I walked the stacks in the library gazing up at shelf after dusty shelf, feeling as if someone had thrown a basket of jewels down on the floor in front of me, sparkling.

I studied Indian History, Sanskrit, Comparative Religion, and then moved to the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at London University so that I could focus on Indian and South East Asian art. SOAS is right next to the British Museum, full of the artistic spoils of empire. The history was horrifying, but at that time I just wanted to know more about this art that, in contrast to my experience of European art history, had cast a spell over me.

It’s pretty difficult to study the history of art in India without constantly coming back to stone carved images. And as so much of the imagery of India was a response to philosophical and religious ideas, that meant mostly studying images that had a specific function in what we now call Jainism, Buddhism and Hinduism. I wrote essays on early Hindu and Buddha images in North India; on Buddha images in Burma, on the walking Buddha at Sukhothai in Thailand.

After a while though, I began to realise that the way that this art history was being presented to me was more or less following the neat, linear path of ‘development’ that I’d experienced in my first year at art school. It wasn’t as tidy as 20th century European art, because the studies started around 1500 BC1, so records and remnants of art and its meanings were often missing or partial. Much of what was presented to us was conjecture on the basis of scant evidence, or textual, representing the perspective of dominant power holders, and a lot of it was based on the work of scholars influenced by colonial attitudes and assumptions. But that’s how it was, and I did my best to feel through the organising frameworks to the nature of the images themselves.

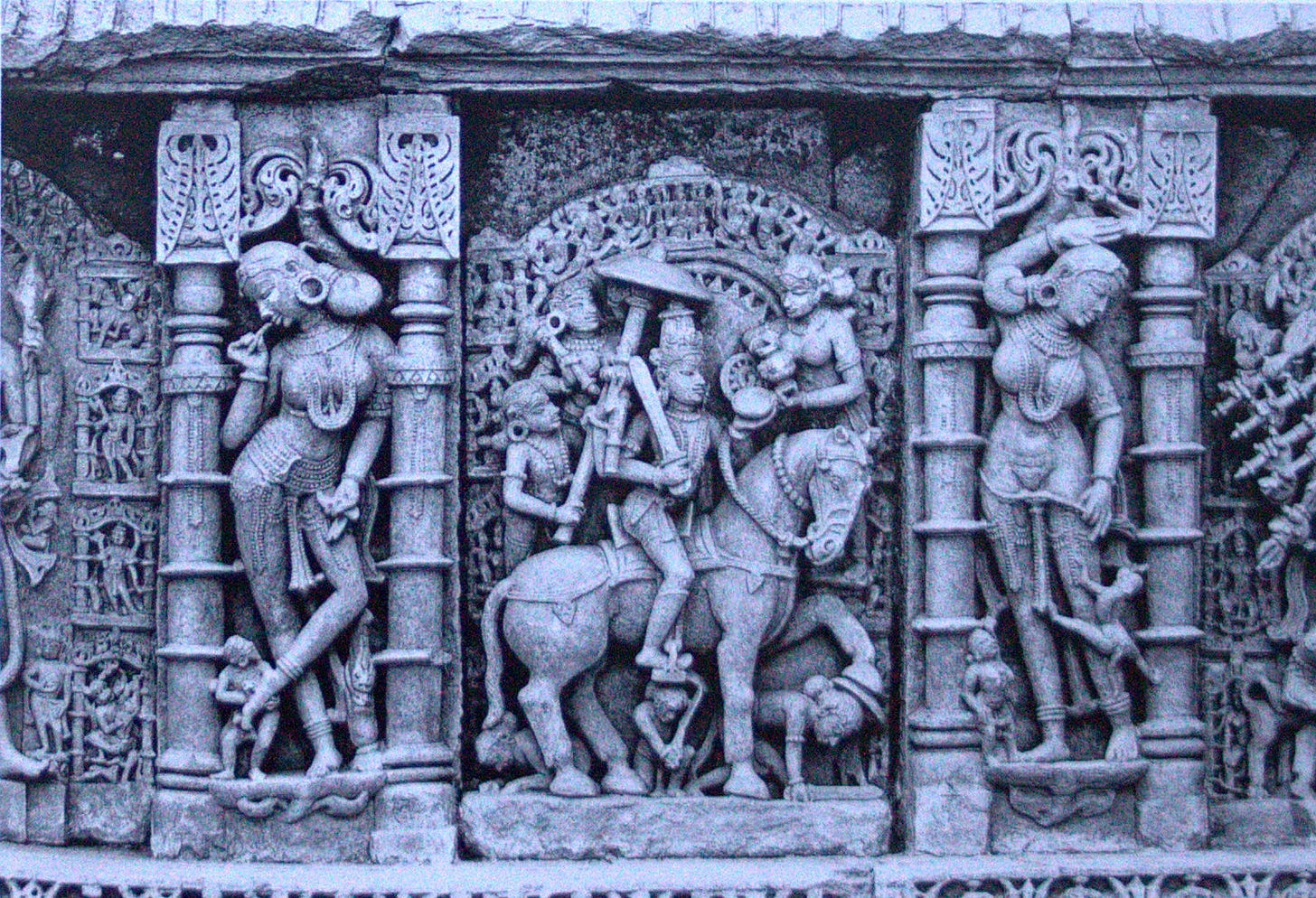

I noticed that art historians tended to engage with images by describing them; either in terms of iconography (‘that’s Vishnu, look, because he’s holding a disc and a conch’) and stories (‘this is the story of Krishna and the butter ball’), or in terms of stylistic developments and changes over time. But I wasn’t retaining either the detail of the shapes and symbols of the iconography, or the mythological stories that this art so often portrayed. I was focussed on the effect different images had on me, on their beauty and distinctiveness; the way, for example, that a curving plant or a tendril of hair moved with such skill and conviction, whilst not actually being representationally ‘true to life’ at all. I was curious about the ideas and principles that were behind the sumptuous forms of nature spirits and guardians, the presence always of animals and plants as well as human forms, and the teeming, crowded nature of compositions that seemed to defy gravity and restructure space.

When you study the origins of Buddhist and Hindu imagery in India around the second century AD, you very quickly come to a comparison of two different image-making centres in North India, Gandhara and Mathura. Gandhara is in the north, near present day Peshawar, and was invaded by Alexander the Great in 326 BC. Mathura is further south, between New Delhi and Agra. The Gandharan images have always attracted a lot of attention because art historians love to see that the Greeks had had an influence here, and consequently many of these images have ended up in museums.

But the images that interested me were the ones from Mathura. Sculptors in Mathura were definitely aware of what was going on in Gandhara, but their images had quite a different feel. The Gandharan Buddha (above) is serene and peaceful, and is regarded to be displaying many features of Greek conventions and aesthetic principles; the folds of the drapery, the treatment of the face, the simplicity of the halo and surrounding features.

The Mathuran Buddha feels quite different. He’s not so much peaceful and sublime as strong and muscular; he looks like someone who has conquered something difficult, sitting up, eyes open, wearing Indian clothes, surrounded by plants and figures and staring straight out at the viewer.

Later I was to learn about a principle of Indian aesthetics which was that an image did not have to be absolutely true to life in terms of outward form and features; that its veracity had to come from whether or not you could sense the movement of prana, breath or life-force, moving through the torso.

Here was what had been whispering to me when I looked at the lichen wave; a version of the power that the Chinese texts talked about which could cause a painted dragon to fly off its paper in a cloud of smoke the minute its eye was finally painted in. Later, reading the Vishnudarmottaram, a text on Indian painting, I was to come across an instruction to painters which said that the viewer should be able to tell whether a painted figure was alive or dead by the quality of their line. This lodged itself in my mind.

This idea about the importance of portraying life force moving through the body took a further metaphysical step for me when I realised that images in temples, the focus of worship and ritual, were in many traditions understood to be literally alive, in the sense of actually manifesting the power of the universe, as God (one supreme being, not ‘a god’ among other gods). Images, and the temples that housed them, were not always just symbols, or pointers, or some kind of vague ‘mediators’ of greater world energies; in some traditions they were a means of interacting with the one, living God, who could be viscerally experienced by his or her devotees. I wanted to know more. I wanted to know what people felt and how they understood their experience of darshan, direct eye to eye contact with the image at the centre of a temple; an image understood to be a living embodiment of a single, all embracing power.

This became the focus of my dissertation, which involved travelling to South India and interviewing ordinary people, sculptors who made the images that were later consecrated and transformed, master architects and temple builders who explained the consecration rituals and how it was that stone could become the living power that moved the universe, and a professor of Vaisnavism at Madras university who was able to explain to me the precise nature of the rituals that could transform matter, along with his own experience of receiving darshan in the presence of God.

Somehow, studying art that I loved, that moved me and fascinated me, took over from any thought of making my own. In India some years before I had wanted to draw trees and tea shops and sacks of grain; everything was beautiful and interesting. When I got back to the UK, however, that feeling disappeared. It makes me think about the link between emotional and existential states and the capacity to make art. The internet is awash with advice about how to be disciplined, how to draw every day, how to knuckle down and get a grip on your procrastination. In my case, though, it’s always been the presence or absence of a state of being which has made it possible to use myself to either make, or not make, my art. I couldn’t just draw ‘to improve my skills’. I had to feel connected, in relationship with the object, the light and the shadow. I had to feel something move inside me, of its own accord.

Studying the sculptured forms of India caused that thing to move. I wasn’t thinking about the fact that in becoming captivated by the power of images in the temple I was following my earlier fascination with the idea that art could have real power in the physical world, that it could create something literally alive with the forces that moved the waves and caused the sun to rise. For me these forces were never any kind of god, but it didn’t bother me that in the Hindu contexts I was studying I had moved into that territory. It all seemed the same to me.

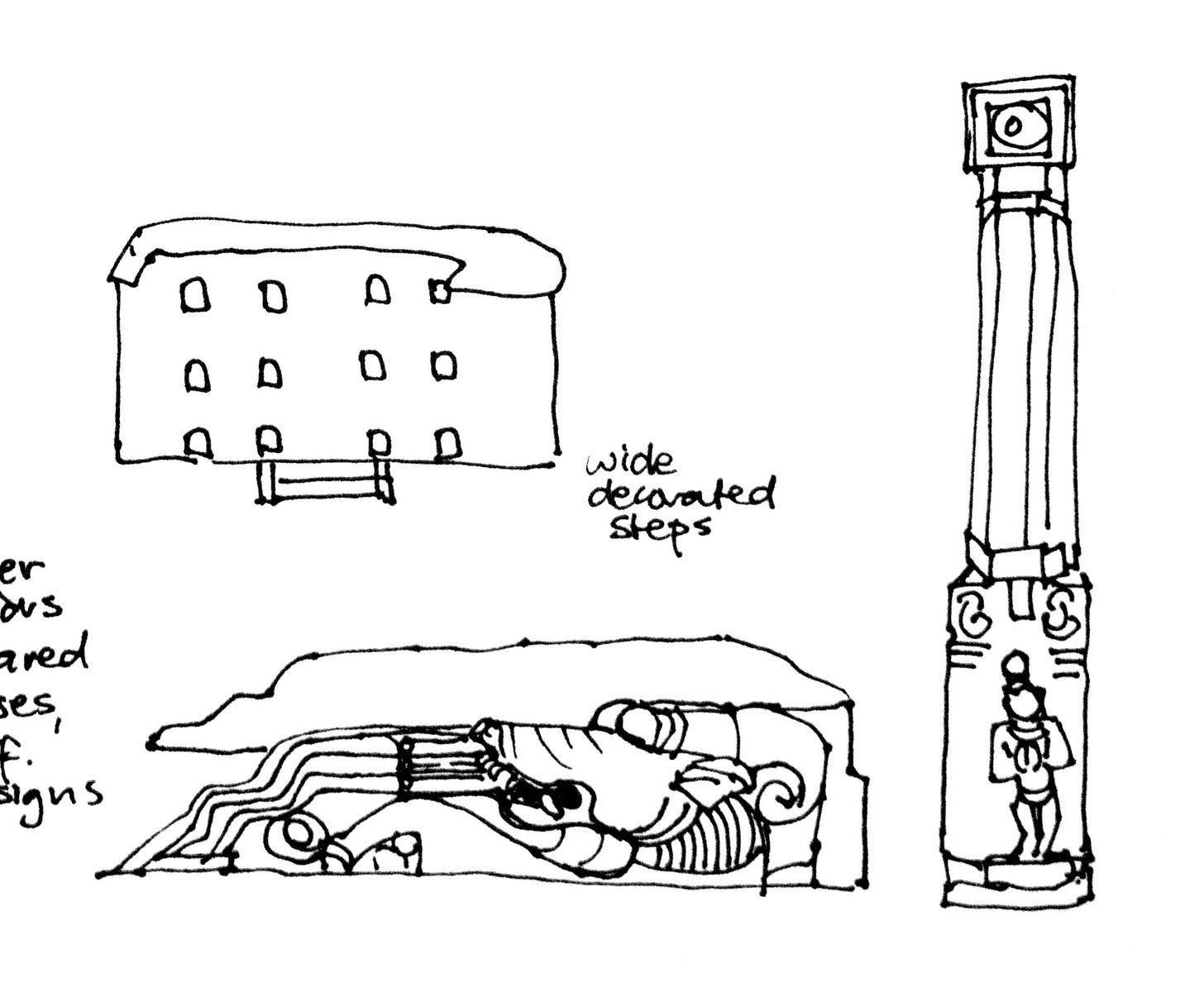

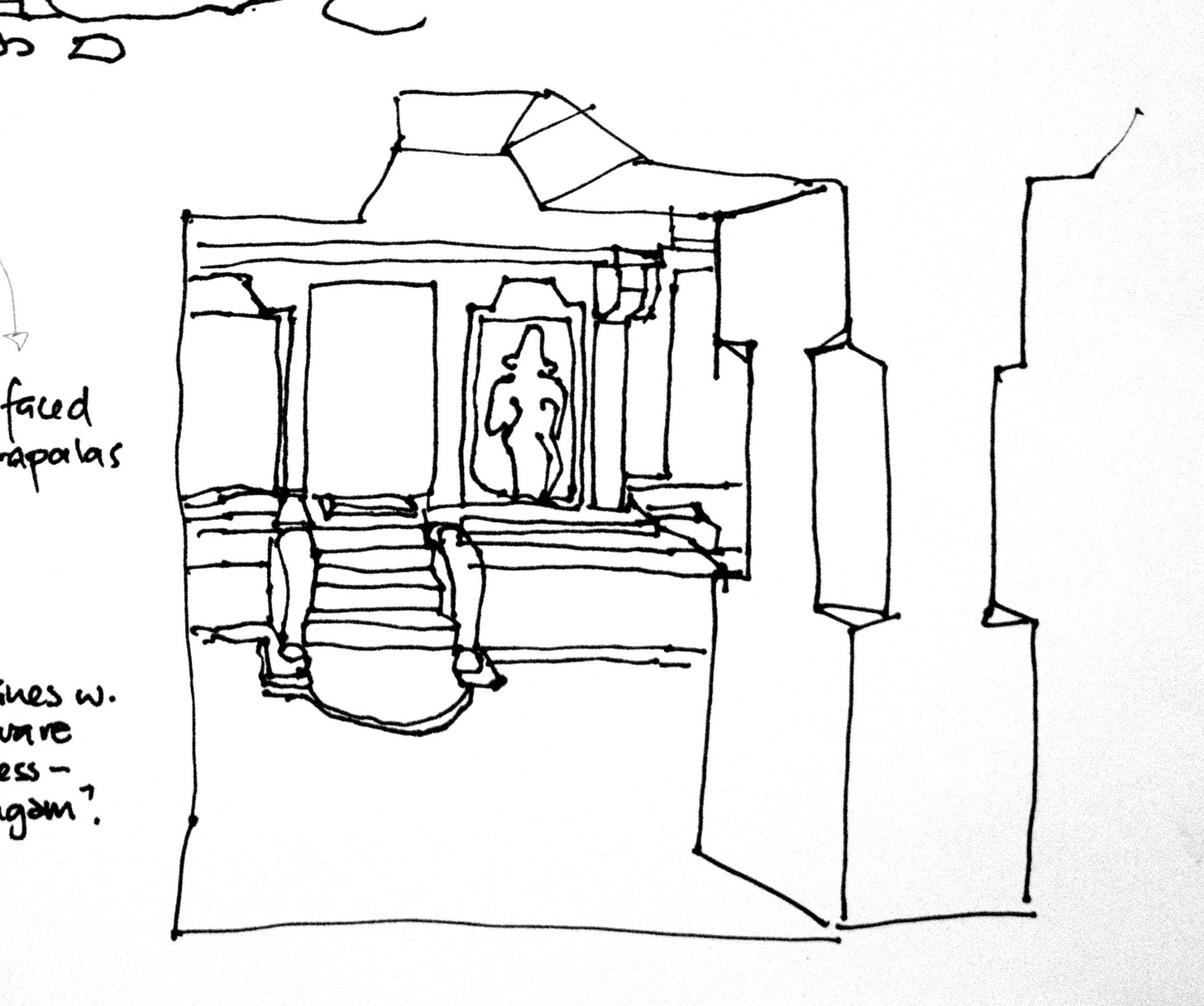

In my final year, as well as the dissertation on the embodiment of God in images, I also studied a number of sites. The first was Chidambaram, the place where Shiva danced the world in and out of existence, and in Madras I was able to see first hand the extraordinary Chola bronzes that are the most famous images of this form. I also went to Mahabalipuram, a mysterious coastal site full of half-finished carved temples and reliefs. At Mahabalipuram, without any prior intention, I did pick up a pen and start to wander over paper in response to what I was seeing.

It was easy, because I had a clear purpose; this time my wandering line allowed me to come closer to mysterious forms that spoke to me of beauty, and story, and intrinsic mysteries that no art historian had been able to solve.

I’m not at all happy with this BC/AD thing, but BCE/CE (Common Era), the attempt to replace it, doesn’t seem to be much better. Both take Christ as the turning point…

Returning from a reading pause - I so enjoy your exquisitely illustrated eloquence, and the worlds + insights you bring through. Thank you for having put the tender effort in to making this all available. I'm enriched by reading + seeing your nourishing offerings! x x x

I don’t know anything about art, but I do really enjoy reading your newsletter because it makes me feel so peaceful and calm. And I’m learning new things :) love the pictures and how you go into details.🩷